Brexit, the Uncivil War: Watering Myths with the Teardrops of the Ruling Class

by Maximilian C. Forte - ZeroAnthropology

21 May, 2019

What have been billed as momentous EU Parliament elections are taking place this week (May 23–26), and it seemed like the right time to review some Brexit films—one is entertainment, the other is a documentary.

The reason for the Brexit theme has to do more with 2019 than with 2016, especially since the Brexit Party, led by Nigel Farage, is supposed to make a massive showing in the EU election.

As expected, long lists of injunctions against the left retaking ground ceded to the right are coming out in The Guardian, chief purveyor of wishes for doing everything wrong again and never learning from mistakes.

Also as expected, Russia is being blamed in advance—because the right thing to do with a really bad conspiracy theory is to keep it alive.

The first movie being reviewed for our Brexit mini-series is Brexit: The Uncivil War (2019), produced by House Productions and shown on HBO and the UK’s Channel 4. It was directed by Toby Haynes, written by James Graham, and stars Benedict Cumberbatch. The plot synopsis is available here, and the official trailer is below.

The movie opens with these words on the screen: “This drama is based on real events and interviews with key people who were there. Some aspects of dialogue, character and scenes have been devised for the purpose of dramatisation”.

The second sentence effectively negates the first. In fact, not only were “some aspects” merely “devised,” they were completely invented, including not just dialogue but also some of the “real events” with “key people” shown in the film. This movie is a mixture of comedy and docudrama, a tepid attempt at reproducing and combining The Big Short and In the Loop, both of which are immeasurably superior films (and probably less insulting to the intelligence of viewers).

The second sentence effectively negates the first. In fact, not only were “some aspects” merely “devised,” they were completely invented, including not just dialogue but also some of the “real events” with “key people” shown in the film. This movie is a mixture of comedy and docudrama, a tepid attempt at reproducing and combining The Big Short and In the Loop, both of which are immeasurably superior films (and probably less insulting to the intelligence of viewers). The movie opens with Dominic Cummings (played by Benedict Cumberbatch), the manager of the Leave campaign. Cummings is immediately shown as eccentric—or perhaps a little of an idiot savant. He opens the film with the line, “Britain makes a noise” (only I heard, “Pudding makes a noise”—perhaps the script should have chosen what I heard, to really emphasize how weird the main character is meant to be, for us).

In one of his fragmented opening monologues, the Cummings character makes some indisputably wise points:

“as a global society we are entering a series of profound economic, cultural, social and political transitions, the like of which the world has never seen…. Massive increase in resource requirements…. A rising tide of religious extremism…. A synthesis of…inter-generational inequality in the West on an historic level”.

At other times, as discussed below, he is a mere puppet for the filmmakers’ polemic against Brexit.

Insight into Elite Myth-Making

The movie can serve as a useful insight into the minds of elite, establishment Remainers, and their ability to dedicate time, energy, and resources into orchestrating a collective international wailing. As has been said repeatedly on this site: those in power would love for us to feel their pain as if it were our own, to make a loss for the transnational capitalist class appear to be our loss, so that we may then rise up and strike out to defend their interests (while annihilating our own).

The movie references the fall of the Berlin wall—with Brexit being the biggest political upset since then. That is a “problem”: the thing about Berlin walls is that they are only supposed to fall in other countries, never in our own. “We” have suffered a basic transgression, a violation of our entitlement to eternal continuity, in spite of the contradictions and conflicts we create and multiply. In other words, it shows you just how deranged our ruling classes have become.

The Ugly Face of Conspiracy

The opening’s main point is to prepare us for the revelation of yet another alleged grand conspiracy, almost like the mythical Russiagate conspiracy theory. We hear forgettable technocrats droning on about UK law and asking Cummings if his actions were within electoral law, or were a threat to democracy. Then the Cummings character, facing the camera, states:

The opening’s main point is to prepare us for the revelation of yet another alleged grand conspiracy, almost like the mythical Russiagate conspiracy theory. We hear forgettable technocrats droning on about UK law and asking Cummings if his actions were within electoral law, or were a threat to democracy. Then the Cummings character, facing the camera, states:“Everyone knows who won. But not everyone knows how”—and that is the point of this movie. And what a miserable little point it is.

In the end, what the filmmakers achieve is another reminder to us that the only real conspiracy we face is the conspiracy of enforced unanimity by state and corporate media—unanimous in their contempt for voters, and for the will of the voters. Abolish the “will” of the voter, by making it appear to be merely the by-product of a sinisterly-devised algorithm and data mining operation, and you thus abolish the voter. No agency, thus no agent. The only real people are the members of the ruling elite.

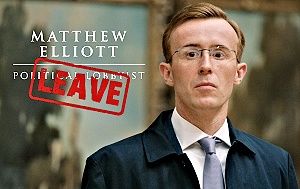

In the end, what the filmmakers achieve is another reminder to us that the only real conspiracy we face is the conspiracy of enforced unanimity by state and corporate media—unanimous in their contempt for voters, and for the will of the voters. Abolish the “will” of the voter, by making it appear to be merely the by-product of a sinisterly-devised algorithm and data mining operation, and you thus abolish the voter. No agency, thus no agent. The only real people are the members of the ruling elite. Appropriate for a conspiracy movie, Douglas Carswell (laughable troglodyte), holds a secret meeting with Matthew Elliott (nervous nerd), in a portrait gallery. I foolishly hoped this would be the end of the silly caricatures, forgetting this is a commercial entertainment product and not a documentary.

Had I prayed for more caricatures, I would have been immediately

satisfied—meet Arron Banks (snarling pig). Only the Boris Johnson

character is a softer version of the real thing, the actual Boris

Johnson being abundantly self-caricaturing already.

Had I prayed for more caricatures, I would have been immediately

satisfied—meet Arron Banks (snarling pig). Only the Boris Johnson

character is a softer version of the real thing, the actual Boris

Johnson being abundantly self-caricaturing already. The usual inflation of grotesque features that one finds in British films, is a simplistic equivalent of bold print, only it is applied to faces. The face is meant to convey meaning—and the meaning here is: villainous conspiracy.

Thus we are shown the faces “behind the [imagined] scenes,” with the hatching of a conspiracy in the UK Independence Party (UKIP, the notorious villain in all establishment narratives second only to “Russia”). “Gunpowder, treason, and plot,” mutters the Cummings character, thus evoking the 1605 Gunpowder plot.

What follows is a lesson from the arch conspirator, Cummings: “How to Change the Course of History. Lesson One: Kill conventional wisdom”. The aim here is to learn from the “true disruptors of Europe”: Napoleon, Otto von Bismarck, and Alexander the Great.

What follows is a lesson from the arch conspirator, Cummings: “How to Change the Course of History. Lesson One: Kill conventional wisdom”. The aim here is to learn from the “true disruptors of Europe”: Napoleon, Otto von Bismarck, and Alexander the Great. The film hurries through the reasons for voter discontent—there were many, and they were diverse—so that we instead come away with the impression that mere “talking points” are being generated by conspirators: the EU seems abstract; immigration is a problem—but what kind of problem? Is it about race? Integration? The levels of immigration?; “people are feeling angrier, left out, ignored”; “don’t think our kids will have a better future than us”; “we spend more time than ever online, but we feel more alone”; “we’re not getting married as much”; “less of us have faith”; “we’re not saving as much”; “we trust less the institutions and people our parents trusted”.

Had the movie drawn this out longer, it would have been a service to the Remainers who seem particularly thick when it comes to trying to understand the opposition and the groundswell of support for Brexit. No luck.

Instead, we are shown the conspiracy, boiling it all down to core talking points: “Loss of national identity. Clear. Sovereignty. Digestible. Loss of community. Simple. Independence. Message repeated over, and over, and over”.

The point is to, “tap into all these little wells of resentment, all these little pressures that have been building up, ignored, over time. We could make this about something more than Europe. Europe just becomes a symbol, a cypher, for everything: every bad thing that is happening, has happened…”.

One reviewer noted a basic contradiction in the movie’s polemic, which involves its magnification of the role of Dominic Cummings. The movie has Cambridge Analytica, Robert Mercer, foreign data firms, big private donors, and every theory possible thrown at the screen as to why Brexit won. Then why did Cummings matter at all?

“Post-Truth”: The Anti-Anthropological Message

The movie also shows us what “post-truth” is meant to mean. Truth is where one appeals to voters’ heads, by using “facts”. The other thing, which has no name other than “post-truth,” appeals to voters’ hearts, using “emotions”. What a poor anthropology this is, where human emotions are divorced from the facts of being human. Any anthropologist who uses the phrase, “post-truth,” does not deserve to be called an anthropologist at all, because they have essentially abolished anthropology. A truth that denies that humans often understand facts emotionally, and that emotions can generate facts, is no truth at all. The real “post-truth” then lies among those who coined the phrase “post-truth” in the first place.

This movie makes no bones about which side owns “the truth”: the Remainers. The movie shows the Remain campaign desperate to counter Brexit with, in their own words, “the truth”. The truth is not shared, equally accessible to all—it is the special preserve of an equally special class, the class that has the Nobel prize-winning economists on their side. The Remainers are shown complaining about the media giving any air time to opponents—there is a deep yearning for censorship. It is all about virtue against democracy.

The Remainers own “expertise”—and the other side owns the ignorant ingrates who forgot their duty was to obey by believing the experts, regardless of their many mounting failures. This is precisely the kind of movie that is not needed now (or ever); it merely invites more scorn and can only validate the resentment of Brexit supporters (and judging from reviews posted online, it has).

The voice of the establishment—Craig Oliver, communications director for Prime Minister David Cameron—describes Cummings as “basically mental”—“just an egotist with a wrecking ball”. And the voters are Frankenstein: “There’s the danger…of having unleashed something which we can’t then control”.

The voters, shown in focus groups, are cast as either ignorant and bumbling fools, or overly opinionated extremists. We are meant to see voters as a pathetic, troubling mass. If we cannot abolish the vote, and the voters, then we should at least try to do so. If moviegoers thought that, then the movie would have succeeded in achieving one of its aims.

One needs to be familiar with the conventions of British entertainment television and the movie industry, obviously in the hands of elites with an axe to grind, to understand how working class voters are shown. This is the same industry that produces things like Coronation Street and The East Enders, or My Name is Lenny (2017), which portray working class people as freakish, mutant rogues. They are either malicious with contorted expressions, or simple dopes who look like they are permanently suffering a stroke. Lacking truth, so they lack goodness and beauty too. We are thus back at “post-truth,” the cherished trope of a neo-Aristotelian class that claims a monopoly on virtue, that tolerates vast inequalities and produces a teleology to justify them.

Does History Need a Sock Puppet?

The filmmakers also resort to using the Cummings character as their sock puppet, having him mouth lines critical of the referendum as “a really dumb idea”—which is what the filmmakers think, and what they want us to think. Here is fake Cummings:

“Referendums are quite literally the worst way to decide anything. They’re divisive. They pretend that complex choices are simple binaries…and we know there are more nuanced and sophisticated ways out there to make political change and reform, not that we live in a nuanced or political age, do we?

“Political discourse has become utterly moronic, thanks to the morons who run it...But there it is. If that is the way it is to be, then I will get us across the line, in whatever way I can”.

This is meant to be the honest, hidden, inside appraisal said in secret—so we think that it’s the truth.

The Cummings character then styles himself as a political “hacker,” entering the “back door,” to “re-program the political system”. It’s all covert, dishonest, and there is a sense of illegality. Meetings are always secret, surreptitious, cloaked—classic conspiracy stuff. Having abolished the will of the voter, the film now abolishes the vote. It’s an expression of a deep desire: for Brexit to have never happened, for the vote to never have been allowed. That’s all. It’s crude, and transparently obvious to even a half-awake viewer.

It was not the only time the filmmakers used Cummings in a contradictory role, that made no sense for the movie. They had this supposed algorithmic genius of online data mining look all disturbed and scared as an American explained to him the new politics of data. He turns and looks at people walking by, using smart phones and tablets, as if they were alien invaders. The final act of sock puppetry was when the filmmakers had Cummings mutter that Nigel Farage is, “a moronic little cunt”—their script, their view. Keeping it classy.

All About Trump?

Of course, there had to be a Trump angle—there is a Trump angle to everything now. We are thus presented with some whispering conspirators from America, in the figures of Robert Mercer (financier), and the Dark Lord himself, Steve Bannon of Breitbart, shown entering the UK to intervene on the side of Brexit. Then we hear “Cambridge Analytica”—the British, not Russian firm that allegedly masterminded Trump’s online campaign. Of course, none of this is true: Robert Mercer never went to offer help with Leave; and, Zack Massingham, the Canadian whose company boasted having a cutting edge date-modeling program, never provided it to the Leave campaign. It’s too bad Joseph Cotten and Orson Welles were not alive to act in this film—their presence could have vastly dignified this poor attempt at film noir. Albert R. Broccoli would have made a more believable film, with more credible villains.

How to Abuse One’s Viewers with Misdirection and Mystification

This movie works by building a chain of misplaced concerns and misidentified problems. That is how mystification works. The “problem” (fake) is with the fear-driven, resentful working class—not their exploitation, marginalization, and even vilification by the privileged. The “problem” (fake) is with nostalgia—not with the current climate being so bad it makes everyday people miss the past. The “problem” (fake) is with hatred—because the problem is always with the response to what has been provoked by those who hold the power.

The “problem” (fake) is with xenophobia—not with a system that taught them pride in being British in the first place, that colonized the world, and for centuries looked down on others with contempt. The fact that huge numbers of refugees were entering Europe—fleeing the regime change wars that Europe helped to manufacture by participating in NATO—only added to the sense of an urgent crisis. Engineering a massive influx of immigrants when locals are locked out of the labour market is a recipe for social peace—exactly nowhere.

The “problem” (not fake, just misleading) was that Jo Cox, Member of Parliament, was assassinated in the lead up to Brexit—the problem was never that Cox herself backed ever escalating violence in Syria to promote catastrophic regime change in the name of “humanitarianism”.

The “problem” (fake) is with the previously apathetic being marshalled to come out and vote—not the fact that they were previously ignored, impeded, and so generally turned off by the dominant politics.

The “problem” (fake) is with crafty data miners who know their business—not with the asymmetry in access to information that props up the political system, or the fact that every political campaign exploits data.

The “problem” (fake) is with the lying politicians on their side—not the lying politicians on all sides, who get away with lying because the system refuses any corrective mechanism to ensure accountability.

And on it goes. When you opt for ideology instead of analysis, you get garbage.

Lessons Not Worth Teaching

So what are the “lessons” of the film? One is “data is power”—actually, data is just data, but anyway. The idea here is that Britain was a “lab experiment” for a new politics based on data mining. Is it bad to gather data about voters? But then why would it be bad? Should one not try to understand voters and what they want?

In a system that bars ordinary people from making decisions even about the basic, immediate, day-to-day aspects of their lives, and that permanently distances and silences them except for a few seconds at a ballot box every few years—how many other ways does the system allow itself to hear from them? Does it matter even, if you can effectively criminalize the mere act of gaining knowledge about voters? Even this movie itself repeats the fact that one side—Remain—had access to the national voter database, while the other side had Cummings try to build an alternative from scratch. If there was a conspiracy, it was here, in this lopsided and unfair distribution of advantages, which the Brexit side overcame. Was Brexit wrong to overcome this data disadvantage?

Did only one side mine online data? Was only one side guilty of “spin”? How much did the Remain campaign spend, compared to the Leave campaign? In fact, the Remain campaign outspent the Leave side by millions of pounds. The movie makes no mention of that fact, nor of the private investors backing Remain, and has little to say about their key influencers. The people with the most votes, spent less money (and won), and they came under investigation for campaign finance violations.

If viewers were truly shocked, chilled, appalled, etc., by what they saw in this movie, then what has stopped them from militating for the total abolition of the advertising industry? Advertisers and PR firms have been doing what this movie shows for generations now. Why the sudden raising of a hue and cry? Why is the outrage so selectively focused on a pinpoint example? Because it’s a dishonest pseudo-critique. That’s one of the things you get when ideology substitutes for analysis.

A second lesson of the film appears to be that the Brexit side was backed by shady financiers—with agendas that are not made clear to us. So who backed the other side? Is there an innocent and pure party here, which the filmmakers neglected to present? Was it the Brexit side that invented the structure of private financing of public political campaigns?

A third lesson has something to do with voter apathy, and the ability of one side to tap into the huge mass of people that regularly refuse to vote in elections in our societies (which would include myself). The crime here appears to have been Brexit’s ability to bring out such persons to vote—as if they found a secret list of dead persons and padded voter rolls. Reducing voter apathy thus becomes something like rigging an election. Yet the quest for the non-voter seems to have failed altogether with Trump: a plurality of eligible voters refused to actually vote. The real winners of the popular vote in the 2016 US presidential elections were precisely those who refused to come out and vote.

The final lesson, with which the movie closes, is that the real problem with the referendum was that it had two sides to it, when ideally it should have had only one: stay. A “crime” was committed by the other side working as if they actually wanted to win. Indeed, the movie closes with the statement that, “in 2018, the Electoral Commission found the Vote Leave campaign guilty of breaking Electoral Law. Leave.EU were subsequently referred to the National Crime Agency for investigation into breaches of Electoral Law”.

Had the country in question been Venezuela, the headlines would have read: “Authoritarian regime cracks down on opponents”. In fact, the investigations had not opened by the time the film was made and, more importantly, the movie itself shows absolutely nothing about how the Leave campaign violated said law. One would think that is a major omission.

Accidentally Intelligent

“We’re asking voters not to reject the status quo, but to return to it”. The only really intelligent point the movie made, was one done quickly and only in passing—it seems to have been by accident, so it may be wrong to ascribe “intelligence” to the filmmakers. The point was this: the real contest in 2016 was not between the status quo and a “disruptive” insurgency, but between two status quos: the present status quo versus those preferring the status quo ante.

In other words, it was effectively a conservative vs. conservative fight. Neither side proposed any revolutionary transformation, of anything really. It was a clash between those clinging to what was known and tried—the only difference being where their preferences fell on an historical timeline. In other words, the Remain vs. Brexit fight was between preservation and restoration, both of which are conservative positions. Now the two sides have been reversed: the pro-Brexit side is struggling to ensure that Britain remains on track to leave, while the pro-Remain side imagines the EU in utopian terms and occupies itself with, “lament, regret, and nostalgia for an imagined arcadian past in which the EU was a land of milk and honey”.

Similarly, in the US Trump was cast as the candidate nostalgically pining away for the lost days of American glory. However today he is campaigning with a new slogan: “Keep America Great”. Joe Biden instead presents himself as driven by the nostalgic need to restore the old order. Just wait until Biden delivers a blistering speech about life in America under Trump—Fox News is certain to denounce him as the “doom and gloom” candidate who offers a picture of “Midnight in America” (just as the others did with Trump).

The best “lesson” of the movie was the one that was unintended, and it is revealed by how the movie backfires on its makers. This movie is a reminder of why dominant interests so richly deserved to lose—and not necessarily that the other side deserved victory. Brexit has been very “profitable” in at least one sense: it has revealed a dysfunctional UK, quasi-governed by inept, visionless elites, incapable of containing a crisis of their own making.

Remember: these are the same elites that turn around and lecture other countries about democracy and good governance, and that bomb other nations in the name of human rights. If anything, Brexit was not a mean enough defeat: much more is needed.

No comments:

Post a Comment