Gorilla Radio is dedicated to social justice, the environment, community, and providing a forum for people and issues not covered in State and Corporate media. The G-Radio can be found at: www.Gorilla-Radio.com, archived at GRadio.Substack.com, and now featuring on Telegram at: Https://t.me/gorillaradio2024. The show's blog is: GorillaRadioBlog.Blogspot.com, and you can check us out on Twitter @Paciffreepress

Saturday, June 29, 2019

Another Colour of Hong Kong Extradition Revolt

Hong Kong: Can Two Million Marchers Be Wrong?

by Kim Petersen - Dissident Voice

June 28th, 2019

In February 2003, protest organizers estimated that nearly 2 million people took to the streets of London in opposition to going to war against Iraq. United States president George W. Bush came across as dismissive of the protestors, likening them to a “focus group.”1 The number of protestors did not deter Bush and United Kingdom prime minister Tony Blair from their path.

The aftermath was that the US, UK, and other allies initiated a lopsided war based on “intelligence and facts [that] were being fixed around the policy” of military action.2 Iraq did not possess weapons-of-mass destruction; it was as United Nations weapons inspector had warned beforehand that Iraq was “fundamentally disarmed.”

What transpired was an act of aggression — which the Nuremberg Tribunal described thusly:

"To initiate a war of aggression, therefore, is not only an international crime; it is the supreme international crime differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole."

Furthermore, the US-led debacle against a sanctions-weakened Iraq is compellingly argued, by lawyers Abdul Haq al-Ani and Tarik al-Ani, as an act of genocide by the US, UK, allies, and the UN Security Council.3

Two Million Demonstrators Take to the Streets of Hong Kong

On 27 June, the Hong Kong Free Press reported about 200 people protesting outside secretary for justice Teresa Cheng’s office. On the following day, a counter demonstration of around 200 people made the rounds of 19 foreign consulates demanding that foreign countries not interfere in the internal affairs of Hong Kong

Just days earlier, crowds estimated at one and two million people took to the streets to protest in Hong Kong. Protest against what?

Fingers point to a gruesome incident that occurred between a Hong Kong couple while on vacation in Taiwan. A young, pregnant woman was murdered, allegedly by her boyfriend. The boyfriend was jailed for the theft of her money and personal effects, but a trial for the killing outside of Hong Kong’s jurisdiction is prevented. And there is no extradition agreement between Hong Kong and Taiwan.

The possibility of a release as early as October of 2019 has been provided as a reason for the expedited passing of an extradition bill.

What was unexpected was that so many Hong Kongers would oppose it.

The protests have been effective in first having amendments made to the bill, and subsequently sidelining the bill, but it may be resurrected for a vote at a later date. The Hong Kong government amended the extradition law to serious criminal offenses only, those carrying a minimum sentence of 7 years’ jail time, for those who committed a crime elsewhere and returned to Hong Kong. A person who commits an offense in Hong Kong would not be extradited to mainland China.

The Boogeyman of Fear

Why the hullabaloo over an extradition bill when Hong Kong already has extradition agreements with 20 countries, including the UK and US?

Why should an extradition agreement with other countries cause such a ruckus? If one peruses the corporate-state media, a clear answer emerges: fear; it is a perceived fear of what China may do to a person extradited to the mainland. Is this a rational or justifiable fear?

The South China Morning Post states, “[C]ritics fear Beijing may abuse the new arrangement to target political activists.”

Germany’s DW cites critics who say China “has a poor legal and human rights record.”

“Protests have been raging in Hong Kong against a controversial extradition bill, which, if approved, would allow suspects to be sent to mainland China for trial.”

Al Jazeera writes that people in Hong Kong fear China’s encroachment on their rights.

The Guardian highlights a Hong Konger who was “waving a large Union Jack flag, a tribute to the British colonial era before the city was handed back to China’s rule, and implicit attack on Beijing.”

The Guardian article claims, “The alarm over the bill underscores many Hong Kong residents’ rising anxiety and frustration over the erosion of civil liberties that have set the city apart from the rest of China.”

The New York Times downplayed Chinese sovereignty over the semi-autonomous Hong Kong by pointing to a large, white banner which read, “This is Hong Kong, not China.”

The Financial Times writes, “Critics fear the law would allow Beijing to seize anyone it likes who sets foot in the territory — from a normal resident to the chief executive of a multinational in transit — and whisk them off to mainland China on trumped up charges.”

What about Edward Snowden?

Back in 2013, ex-CIA employee Edward Snowden left the US for Hong Kong with a thumb-drive stash of secret NSA documents, which he turned over to some hand-picked journalists. Snowden was not beyond the reach of the US in Hong Kong, and the American government sought his extradition. Snowden, however, was allowed to depart Hong Kong for Moscow. Apparently, the Americans “had mucked up the legal paperwork.”

Hong Kong had no choice but to let the 30-year-old leave for “a third country through a lawful and normal channel.”

Those refugees in Hong Kong who helped Snowden elude apprehension have not fared as well as Snowden. Human-rights lawyer Robert Tibbo described the situation bluntly: “Refugees are marginalized to such an extent, that they are Hong Kong’s own version of Untouchables.”

Yet, despite what is transpiring in their own backyard, Hong Kongers are in the streets saying they fear what might happen to those who might be extradited to mainland China.

What about Julian Assange?

Hong Kongers and the state-corporate media are expressing fear about what China may do. But what about two countries that Hong Kong has an extradition agreement with — the US and the UK? One only need point to the current egregious abuses meted out to Julian Assange to dispel any notion of justice. And why is Assange’s extradition being sought? For exposing US war crimes!

Relations with Mainland China

China’s chairman Xi Jinping is unremitting in his battle against corruption, but also his political platform includes “promot[ing] social fairness and justice as core values.”4 Is this something to fear?

There is the case of the disappearance of Hong Kong booksellers. There is also concern about the arrest of human rights lawyers in China. I am not about to state that the application of the law in China is perfect. But where is justice perfect? China does practice censorship, but freedom to speak has limits. One instance of when censorship is justified: to prevent the dissemination and spread of disinformation. Consider the image at left, while the actual size of the demonstrations were massive, the image was “heavily edited — cropped and mirrored — to multiply the size of the crowd.” It has gone viral with subsequent republications failing to mention the editing and cropping.

Then there is the omission of information, such as the purported funding of the protests in Hong Kong by the US government and a notorious CIA-affiliated NGO, the National Endowment for Democracy. This is backed by various western governments expressing sympathy for the Hong Kong protestors.

The often bandied-about criticisms concerning China are of authoritarianism, lack of democracy, and lack of freedom.

Is China authoritarian?

China, through the Communist Party of China, defines itself as a state practicing socialism with Chinese characteristics. It promotes as its core values: prosperity, democracy, civility, harmony, freedom, equality, justice, the rule of law, patriotism, dedication, integrity, and friendliness. China practices utilitarianism aiming its policies at what best benefits the majority of its citizens. China promotes peace and harmony; it emphasizes diplomacy and avoidance of war.

To allays fears, Xi said in a speech in Berlin:

"As China continues to grow, some people start to worry. Some take a dark view of China and assume that it will inevitably become a threat as it develops further. They even portray China as being the terrifying Mephisto who will someday suck the soul of the world. Such absurdity couldn’t be more ridiculous, yet some people, regrettably, never tire of preaching it. This shows prejudice is indeed hard to overcome….

"The pursuit of peace, amity and harmony is an integral part of the Chinese character which runs deep in the blood of the Chinese people. This can be evidenced by axioms from ancient China such as: “A warlike state, however big it may be, will eventually perish.”"5

Democracy? Wei Ling Chua in his book, Democracy: What the West Can Learn from China, sought to compare and contrast the effectiveness of western and Chinese political systems scientifically. The assumption is that the well-being of the citizenry is the raison d’être of a government. To determine this, Chua gauged government responsiveness to the needs of the people during a disaster. The response of the Australian and American governments compared unfavorably with the Chinese government’s response to disasters. Chua writes this is because “… the culture and beliefs of the Communist Party in China is more people-oriented than those of the capitalist elites in the West.”6 Besides, what democracy did Hong Kong enjoy under British until the time of a handover approached? Is not the imposition of colonial status through war to facilitate opium exports a total abnegation of democracy and freedom?7

I have lived in China for a number of years, and I feel just as free here as anywhere. Of course, I wouldn’t stand on a soapbox with a megaphone and shout anti-China slogans, but I wouldn’t do that anywhere about that country’s government. The right to peaceful protest, however, should be respected. The Chinese people around me do not complain of feeling unfree. As already stated, there is censorship. Very few people here are aware of the protests taking place in Hong Kong. But freedom is not just about speech. What about freedom from poverty? One in five Hong Kongers live in poverty, a number that is on the increase in Hong Kong. Contrariwise, the year 2020 is targeted as the year that poverty is eliminated in China.

Etiology

Charles Chow (pseudonym for an American who lives on and off in Hong Kong) gave his perspective:

"The big issue isn’t the [extradition] bill at all or even the relative lack of democracy in Hong Kong…. It’s two fundamental issues that have existed since the colonial era, but worsened since the handover: a growing wealth gap and the lack of affordable housing. The government hasn’t done much to resolve them and neither has China. Their failure to tackle these problems has made Hong Kongers less trustful of them and more irritable overall. Therefore, even small controversies will point back to these bigger issues."

I agree with Chow’s identification of two fundamental issues. However, I fail to see why in a one country, two systems situation that Beijing should be held responsible for the resolution of problems associated with the Hong Kong system of governance. Moreover, the yawning chasm in the percentage of those living in poverty under the system in Hong Kong versus the system in mainland China (under 1%, for a much larger territory with a huge population, therefore, posing greater challenges for effective governance) suggests the Hong Kong system is majorly flawed in at least one important aspect.

"Now it’s 22 years after the handover–an entire generation has passed. The legacy of colonialism will linger for a while, but the current government has had two decades to resolve any problem the British left behind. Hong Kong’s economy is still robust, but its gains have been unequally distributed."8

Chow continues:

"Its housing prices are just obscene–especially given the size and build quality of the properties they represent. Neither problem shows any sign of abating and both are, in fact, getting worse. Thus, even some Hong Kongers who are pro-Beijing have expressed concern over both problems because they know neither discriminates by political affiliation. Where they differ from the pro-democracy crowd is how to resolve them.

"The pro-democracy folks believe giving more people a say in how Hong Kong operates (in other words, more democracy) is the solution. The pro-Beijing folks think the current government, along with China, should be able to do something. But this government, beholden as it is to the tycoons and China (such an odd couple), isn’t going to tackle these problems. Because it won’t, it has created a growing body of restless Hong Kongers, many of whom were once apolitical and probably even opposed Occupy in 2014.

"It didn’t have to be this way. In a fairer world, Hong Kong would have a manageable wealth gap and be able to provide affordable housing for most of its people. In such a scenario, even most people who aren’t crazy about China would accept its sovereignty and foreign attempts to get them to protest Chinese rule would go nowhere.

"Even if an extradition bill were proposed, there’d be fewer people showing a concern over it."

Epilogue

Imagine if a country were to invade and occupy Hawai’i for the next century9, after which Hawai’i would be semi-liberated from occupation. Would Hawaiians wish to rejoin the US? Might not new systems, cultures, and languages have been injected during the occupation/colonization have affected the mindset of the later generations?

The roots of the opposition that many Hong Kongers feel toward the extradition bill arguably lies further back in history. Clear-minded logic leads to the realization that if Britain had not started the Opium Wars (a crime of aggression) and occupied Hong Kong, thus severing Hong Kong from Beijing’s rule, there never would have been a need for the difficulties that arise from the one country, two systems currently in place. A de facto city-state would never have been able to become a haven for fugitives from the central government. Hong Kong would have remained a part of China. The same logic holds true in the case of Taiwan. If Japan had not occupied Taiwan, and if the US had not intervened to protect the Guomindang remnants that fled across the Taiwan Strait, Taiwan would likeliest have remained a part of China to this day.

The source of the current tensions in Hong Kong did not originate in Beijing (unless one blames Beijing for being too militarily weak to protect its territorial integrity and prevent its citizens from being transformed into drug addicts).

This is missing from much of the western corporate-state media news. While China seeks to safeguard sovereignty over its landmass, Britain holds fast to its enclave in Northern Ireland. It ignores justice and maintains an ethnic cleansing that it and the US imposed on the people of the Chagos archipelago. The US itself is a nation erected through the denationalization of Indigenous nations.10

How is it then that western nations and their western media have a moral leg to stand on when criticizing other nations, such as China, for fear of criminality that pale in comparison to those crimes that the western nations have committed?

Can two million marchers be wrong? They are not wrong about the right to march or the right to protest. Are they wrong to oppose the extradition of persons for serious offenses to China? Are they wrong to fear China? Do they genuinely fear China? This fear of mainland China is seemingly so negligible that 6.9 million of the 7.4 million Hong Kongers hold a Homeland Return Permit to ease travel to and from China. Is it sensible for people to travel to a jurisdiction that they fear?

The comparison is stark.

Compare protesting the launching of a war wherein upwards of 600,000 people were killed11 (now being killed that is something that most people fear) to protesting the upholding of law to ensure murderers should face justice. If, indeed, China is governed by a scofflaw government, then there is a justification for having fear. But before casting final judgement, western countries ought to look deeply into the mirror, the mirror that reflects the not-so-long-ago devastations of Palestine, Yugoslavia, Iraq, Libya, Syria, and other lands. China’s last battles were with India and Viet Nam many decades ago. The Communist Party of China (CPC) states an abhorrence of wars and promotes peaceful resolution of differences.5

The CPC acknowledges that it is dependent on the support of the people; without it the party will fall. The CPC’s raison d’être is the well-being of the people, what is called the Chinese Dream.

It would be foolish and contradictory for Beijing to upset Hong Kongers. Harmony is, after all, a core value of socialism. The one country, two systems is due to expire in 2047. Likewise, Hong Kong has nothing to gain from irritating Beijing. However, should Hong Kong integrate into the economic system of China, it stands to see the elimination of poverty in the former British colony.

Notes

Said Bush, “First of all, you know, size of protests–it’s like deciding, `Well, I’m going to decide policy based upon a focus group.’ The role of a leader is to decide policy based upon, in this case, the security of the people.” []

As revealed in the Downing Street Memo. The website, however, no longer is accessible. The page reads: This Account has been suspended. The memo is available at this pdf. []

See Abdul Haq al-Ani and Tarik al-Ani, Genocide in Iraq: The Case Against the UN Security Council and Member States. Review. []

“We should address the people’s proper and lawful demands on matters affecting their interests, and improve the institutions that are important for safeguarding their vital interests.” Xi Jinping, The Governance of China (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2014): 35%. []

Xi Jinping, “China’s Commitment to Peaceful Development” in The Governance of China: 35%. [] []

Wei Ling Chua, Democracy: What the West Can Learn from China (2013): location 1214. Review. []

See Samuel Merwin, Drugging a Nation: The Story of China and the Opium Curse (Toronto: Fleming H. Revell Co, 1908. []

The income distribution in Hong Kong has become extraordinarily high. — KP []

Never mind that this is what happened so that the US mainland could depose the Hawaiian monarchy. []

See Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States (Beacon Press, 2015). Review. []

Burnham G, Lafta R, Doocy S, and Roberts L, “Mortality after the 2003 invasion of Iraq: a cross-sectional cluster sample survey,” Lancet: 368(9545), 21 October 2006: 1421-8. []

Kim Petersen is a former co-editor of the Dissident Voice newsletter. He can be reached at: kimohp@gmail.com. Twitter: @kimpetersen.

Read other articles by Kim.

Wednesday, June 26, 2019

Peace in Our Time, Anyone?

The Antiwar Movement No One Can See: Will It Put a Crimp in the War on Terror?

by Allegra Harpootlian - TomDispatch

June 23, 2019

Those like me working against America’s seemingly endless wars wondered why the subject merited so little discussion, attention, or protest. Was it because the still-spreading war on terror remained shrouded in government secrecy? Was the lack of media coverage about what America was doing overseas to blame? Or was it simply that most Americans didn’t care about what was happening past the water’s edge? If you had asked me two years ago, I would have chosen “all of the above.” Now, I’m not so sure.

After the enormous demonstrations against the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the antiwar movement disappeared almost as suddenly as it began, with some even openly declaring it dead. Critics noted the long-term absence of significant protests against those wars, a lack of political will in Congress to deal with them, and ultimately, apathy on matters of war and peace when compared to issues like health care, gun control, or recently even climate change.

Tomgram: Allegra Harpootlian, Ending the Forever Wars?

I remember well the antiwar movement of the Vietnam era. I was in it and it was distinctly in the streets, big time. I was typical, for instance, in traveling to Washington in October 1967 for a march on the Pentagon, which proved to be the largest antiwar protest ever staged to that point -- a crowd so vast I had never seen the likes of it before. And I returned to the capital a year or two later for a far more chaotic antiwar demonstration in which I remember having to choose between staying with a bold friend eager to rush further into the tear-gas-laced streets around the Washington Mall or run for it -- alone. (I reluctantly chose to stay.) And then there were all the little moments of work and opposition over so many years, the moments when you weren’t with crowds of people in those streets, but you were still focused on opposing that American war from hell.

And then, of course, I remember that second antiwar moment of vast crowds on a global scale in the winter and early spring of 2003, when I found myself once again marching with staggering numbers of other people against a grim American war, this time one still to come. It was already obvious, though, that the top officials of the Bush administration were intent on invading Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, no matter what. Still, I suspect the crowds of demonstrators then put even the Vietnam protests to shame. Strangely, however, when that war began and essentially didn’t end but spread, when it came to embroil, in one way or another, much of the Greater Middle East and then parts of Africa, when the Arab Spring broke out, Syria cracked open, and ISIS appeared -- when, to use a phrase of former Arab League head Amr Mussa, it was clearer that we had passed through “the gates of Hell” in the Greater Middle East -- it seemed as if no one in the U.S. was in the streets or anywhere else.

Yes, there were some places like TomDispatch that continued to focus on those never-ending wars and the chaos, death, displacement, and destruction they caused, but generally it felt -- at least to me -- as if, in a period of never-ending and disastrous conflicts across vast (and distant) stretches of the planet, the American public was nowhere to be found. That’s why, when I read TomDispatch regular Allegra Harpootlian’s take on the situation, I found a certain genuine hope there. No, there still isn’t an antiwar movement in the streets of America, but that doesn’t mean nothing is happening, nothing is forming, nothing is brewing when it comes to our twenty-first-century wars from hell, not if you look in the right way and in the right places. Check out her piece and see what I mean. Tom

The Antiwar Movement No One Can See: Will It Put a Crimp in the War on Terror?

by Allegra Harpootlian

The pessimists have been right to point out that none of the plethora of marches on Washington since Donald Trump was elected have had even a secondary focus on America’s fruitless wars. They’re certainly right to question why Congress, with the constitutional duty to declare war, has until recently allowed both presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump to wage war as they wished without even consulting them. They’re right to feel nervous when a national poll shows that more Americans think we’re fighting a war in Iran (we’re not) than a war in Somalia (we are).

But here’s what I’ve been wondering recently: What if there’s an antiwar movement growing right under our noses and we just haven’t noticed? What if we don’t see it, in part, because it doesn’t look like any antiwar movement we’ve even imagined?

If a movement is only a movement when people fill the streets, then maybe the critics are right. It might also be fair to say, however, that protest marches do not always a movement make. Movements are defined by their ability to challenge the status quo and, right now, that’s what might be beginning to happen when it comes to America’s wars.

What if it’s Parkland students condemning American imperialism or groups fighting the Muslim Ban that are also fighting the war on terror? It’s veterans not only trying to take on the wars they fought in, but putting themselves on the front lines of the gun control, climate change, and police brutality debates. It’s Congress passing the first War Powers Resolution in almost 50 years. It’s Democratic presidential candidates signing a pledge to end America’s endless wars.

For the last decade and a half, Americans -- and their elected representatives -- looked at our endless wars and essentially shrugged. In 2019, however, an antiwar movement seems to be brewing. It just doesn't look like the ones that some remember from the Vietnam era and others from the pre-invasion-of-Iraq moment. Instead, it's a movement that’s being woven into just about every other issue that Americans are fighting for right now -- which is exactly why it might actually work.

A Veteran’s Antiwar Movement in the Making?

During the Vietnam War of the 1960s and early 1970s, protests began with religious groups and peace organizations morally opposed to war. As that conflict intensified, however, students began to join the movement, then civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. got involved, then war veterans who had witnessed the horror firsthand stepped in -- until, with a seemingly constant storm of protest in the streets, Washington eventually withdrew from Indochina.

You might look at the lack of public outrage now, or perhaps the exhaustion of having been outraged and nothing changing, and think an antiwar movement doesn’t exist. Certainly, there’s nothing like the active one that fought against America’s involvement in Vietnam for so long and so persistently. Yet it’s important to notice that, among some of the very same groups (like veterans, students, and even politicians) that fought against that war, a healthy skepticism about America’s twenty-first-century wars, the Pentagon, the military industrial complex, and even the very idea of American exceptionalism is finally on the rise -- or so the polls tell us.

Right after the midterms last year, an organization named Foundation for Liberty and American Greatness reported mournfully that younger Americans were “turning on the country and forgetting its ideals,” with nearly half believing that this country isn’t “great” and many eyeing the U.S. flag as “a sign of intolerance and hatred.” With millennials and Generation Z rapidly becoming the largest voting bloc in America for the next 20 years, their priorities are taking center stage. When it comes to foreign policy and war, as it happens, they’re quite different from the generations that preceded them. According to the Chicago Council of Global Affairs,

“Each successor generation is less likely than the previous to prioritize maintaining superior military power worldwide as a goal of U.S. foreign policy, to see U.S. military superiority as a very effective way of achieving U.S. foreign policy goals, and to support expanding defense spending. At the same time, support for international cooperation and free trade remains high across the generations. In fact, younger Americans are more inclined to support cooperative approaches to U.S. foreign policy and more likely to feel favorably towards trade and globalization.”

Although marches are the most public way to protest, another striking but understated way is simply not to engage with the systems one doesn’t agree with. For instance, the vast majority of today’s teenagers aren’t at all interested in joining the all-volunteer military. Last year, for the first time since the height of the Iraq war 13 years ago, the Army fell thousands of troops short of its recruiting goals. That trend was emphasized in a 2017 Department of Defense poll that found only 14% of respondents ages 16 to 24 said it was likely they’d serve in the military in the coming years. This has the Army so worried that it has been refocusing its recruitment efforts on creating an entirely new strategy aimed specifically at Generation Z.

In addition, we’re finally seeing what happens when soldiers from America’s post-9/11 wars come home infused with a sense of hopelessness in relation to those conflicts. These days, significant numbers of young veterans have been returning disillusioned and ready to lobby Congress against wars they once, however unknowingly, bought into. Look no farther than a new left-right alliance between two influential veterans groups, VoteVets and Concerned Veterans for America, to stop those forever wars. Their campaign, aimed specifically at getting Congress to weigh in on issues of war and peace, is emblematic of what may be a diverse potential movement coming together to oppose America’s conflicts. Another veterans group, Common Defense, is similarly asking politicians to sign a pledge to end those wars. In just a couple of months, they’ve gotten on board 10 congressional sponsors, including freshmen heavyweights in the House of Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ilhan Omar.

And this may just be the tip of a growing antiwar iceberg. A misconception about movement-building is that everyone is there for the same reason, however broadly defined. That’s often not the case and sometimes it’s possible that you’re in a movement and don’t even know it. If, for instance, I asked a room full of climate-change activists whether they also considered themselves part of an antiwar movement, I can imagine the denials I’d get. And yet, whether they know it or not, sooner or later fighting climate change will mean taking on the Pentagon’s global footprint, too.

Think about it: not only is the U.S. military the world’s largest institutional consumer of fossil fuels but, according to a new report from Brown University’s Costs of War Project, between 2001 and 2017, it released more than 1.2 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere (400 million of which were related to the war on terror). That’s equivalent to the emissions of 257 million passenger cars, more than double the number currently on the road in the U.S.

A Growing Antiwar Movement in Congress

One way to sense the growth of antiwar sentiment in this country is to look not at the empty streets or even at veterans organizations or recruitment polls, but at Congress. After all, one indicator of a successful movement, however incipient, is its power to influence and change those making the decisions in Washington. Since Donald Trump was elected, the most visible evidence of growing antiwar sentiment is the way America’s congressional policymakers have increasingly become engaged with issues of war and peace. Politicians, after all, tend to follow the voters and, right now, growing numbers of them seem to be following rising antiwar sentiment back home into an expanding set of debates about war and peace in the age of Trump.

In campaign season 2016, in an op-ed in the Washington Post, political scientist Elizabeth Saunders wondered whether foreign policy would play a significant role in the presidential election. “Not likely,” she concluded. “Voters do not pay much attention to foreign policy.” And at the time, she was on to something. For instance, Senator Bernie Sanders, then competing for the Democratic presidential nomination against Hillary Clinton, didn’t even prepare stock answers to basic national security questions, choosing instead, if asked at all, to quickly pivot back to more familiar topics. In a debate with Clinton, for instance, he was asked whether he would keep troops in Afghanistan to deal with the growing success of the Taliban. In his answer, he skipped Afghanistan entirely, while warning only vaguely against a “quagmire” in Iraq and Syria.

Heading for 2020, Sanders is once again competing for the nomination, but instead of shying away from foreign policy, starting in 2017, he became the face of what could be a new American way of thinking when it comes to how we see our role in the world.

In February 2018, Sanders also became the first senator to risk introducing a war powers resolution to end American support for the brutal Saudi-led war in Yemen. In April 2019, with the sponsorship of other senators added to his, the bill ultimately passed the House and the Senate in an extremely rare showing of bipartisanship, only to be vetoed by President Trump. That such a bill might pass the House, no less a still-Republican Senate, even if not by a veto-proof majority, would have been unthinkable in 2016. So much has changed since the last election that support for the Yemen resolution has now become what Tara Golshan at Vox termed “a litmus test of the Democratic Party’s progressive shift on foreign policy.”

Nor, strikingly enough, is Sanders the only Democratic presidential candidate now running on what is essentially an antiwar platform. One of the main aspects of Elizabeth Warren’s foreign policy plan, for instance, is to “seriously review the country’s military commitments overseas, and that includes bringing U.S. troops home from Afghanistan and Iraq.” Entrepreneur Andrew Yang and former Alaska Senator Mike Gravel have joined Sanders and Warren in signing a pledge to end America’s forever wars if elected. Beto O’Rourke has called for the repeal of Congress’s 2001 Authorization to Use Military Force that presidents have cited ever since whenever they’ve sent American forces into battle. Marianne Williamson, one of the many (unlikely) Democratic candidates seeking the nomination, has even proposed a plan to transform America’s “wartime economy into a peace-time economy, repurposing the tremendous talents and infrastructure of [America’s] military industrial complex... to the work of promoting life instead of death.”

And for the first time ever, three veterans of America’s post-9/11 wars -- Seth Moulton and Tulsi Gabbard of the House of Representatives, and South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg -- are running for president, bringing their skepticism about American interventionism with them. The very inclusion of such viewpoints in the presidential race is bound to change the conversation, putting a spotlight on America’s wars in the months to come.

Get on Board or Get Out of the Way

When trying to create a movement, there are three likely outcomes: you will be accepted by the establishment, or rejected for your efforts, or the establishment will be replaced, in part or in whole, by those who agree with you. That last point is exactly what we’ve been seeing, at least among Democrats, in the Trump years. While 2020 Democratic candidates for president, some of whom have been in the political arena for decades, are gradually hopping on the end-the-endless-wars bandwagon, the real antiwar momentum in Washington has begun to come from new members of Congress like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) and Ilhan Omar who are unwilling to accept business as usual when it comes to either the Pentagon or the country’s forever wars. In doing so, moreover, they are responding to what their constituents actually want.

As far back as 2014, when a University of Texas-Austin Energy Poll asked people where the U.S. government should spend their tax dollars, only 7% of respondents under 35 said it should go toward military and defense spending. Instead, in a “pretty significant political shift” at the time, they overwhelmingly opted for their tax dollars to go toward job creation and education. Such a trend has only become more apparent as those calling for free public college, Medicare-for-all, or a Green New Deal have come to realize that they could pay for such ideas if America would stop pouring trillions of dollars into wars that never should have been launched.

The new members of the House of Representatives, in particular, part of the youngest, most diverse crew to date, have begun to replace the old guard and are increasingly signalling their readiness to throw out policies that don’t work for the American people, especially those reinforcing the American war machine. They understand that by ending the wars and beginning to scale back the military-industrial complex, this country could once again have the resources it needs to fix so many other problems.

In May, for instance, Omar tweeted, “We have to recognize that foreign policy IS domestic policy. We can't invest in health care, climate resilience, or education if we continue to spend more than half of discretionary spending on endless wars and Pentagon contracts. When I say we need something equivalent to the Green New Deal for foreign policy, it's this.”

A few days before that, at a House Committee on Oversight and Reform hearing, Ocasio-Cortez confronted executives from military contractor TransDigm about the way they were price-gouging the American taxpayer by selling a $32 “non-vehicular clutch disc” to the Department of Defense for $1,443 per disc. “A pair of jeans can cost $32; imagine paying over $1,000 for that,” she said. “Are you aware of how many doses of insulin we could get for that margin? I could’ve gotten over 1,500 people insulin for the cost of the margin of your price gouging for these vehicular discs alone.”

And while such ridiculous waste isn’t news to those of us who follow Pentagon spending closely, this was undoubtedly something many of her millions of supporters hadn’t thought about before. After the hearing, Teen Vogue created a list of the “5 most ridiculous things the United States military has spent money on,” comedian Sarah Silverman tweeted out the AOC hearing clip to her 12.6 million followers, Will and Grace actress Debra Messing publicly expressed her gratitude to AOC, and according to Crowdtangle, a social media analytics tool, the NowThis clip of her in that congressional hearing garnered more than 20 million impressions.

Not only are members of Congress beginning to call attention to such undercovered issues, but perhaps they’re even starting to accomplish something. Just two weeks after that contentious hearing, TransDigm agreed to return $16.1 million in excess profits to the Department of Defense. “We saved more money today for the American people than our committee’s entire budget for the year,” said House Oversight Committee Chair Elijah Cummings.

Of course, antiwar demonstrators have yet to pour into the streets, even though the wars we’re already involved in continue to drag on and a possible new one with Iran looms on the horizon. Still, there seems to be a notable trend in antiwar opinion and activism. Somewhere just under the surface of American life lurks a genuine, diverse antiwar movement that appears to be coalescing around a common goal: getting Washington politicians to believe that antiwar policies are supportable, even potentially popular. Call me an eternal optimist, but someday I can imagine such a movement helping end those disastrous wars.

Allegra Harpootlian, a TomDispatch regular, is a senior media associate at ReThink Media where she works with leading experts and organizations at the intersection of national security, politics, and the media. She principally focuses on U.S. drone policies and related use-of-force issues. She is also a political partner with the Truman National Security Project. Find her on Twitter @ally_harp.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel (the second in the Splinterlands series) Frostlands, Beverly Gologorsky's novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt's A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy's In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower's The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Copyright 2019 Allegra Harpootlian

Thousands Killed: Media Silence on US Venezuela Sanctions Toll

So Who Is Reporting That Trump Sanctions Have Killed Thousands of Venezuelans?

by Joe Emersberger - FAIR

June 26, 2019

Protest march, (Venezuelanalysis report 4/26/19) on the CEPR study

(photo: @ChuckModi1/Twitter)

I wrote on June 14 about Reuters burying (for over a month) a study (CEPR, 4/25/19) by prominent economists Jeffrey Sachs and Mark Weisbrot that links economic sanctions President Donald Trump imposed on Venezuela in August 2017 to an estimated 40,000 deaths by the end of 2018. As of January 2019, Trump made the sanctions even more severe.

The study is the clearest evidence of the devastating impact US policy is having on the people of Venezuela. Below is a list of English-language outlets that, according to the Nexis news database, mentioned the study as of June 17. They are overwhelmingly non-US outlets:

CE Noticias Financieras (English) (4 mentions)

Sputnik News Service (Russia) (3)

Iran Daily (2)

Bangladesh Government News

China Daily

China Daily (US Edition)

Crikey (Australia)

Edmonton Sun (Canada)

Eurasia Review (US)

Kashmir Times (India)

Newsbank (Washington news sources)

PM News (Nigeria)

Press TV (Iran)

Pressenza International Press Agency (Ecuador)

States News Service (US)

The Nation (US)

To be fair, Nexis doesn’t seem to catch Reuters articles or reprints in other outlets. Reuters did finally mention the study at the end of an article (6/9/19). Telesur English reported on the study, but is not on the list

above.

The Independent (4/26/19) had one of the few reports in

corporate media that focused on the CEPR study.

Also missing above is an excellent news article that Andrew Buncombe wrote for the UK Independent (4/26/19) the day after the study was released. Having followed Buncombe’s reporting (as well as his Twitter timeline) for many years, I wasn’t surprised.

Aside from monitoring non-US outlets to catch important facts that are “missed” by the US media about Washington’s role in the word, readers would be well-advised to watch for individual journalists who, even within corporate media, are willing to break from the herd.

Alternative outlets that covered the study (VenezuelAnalysis.com, The Canary, FAIR.org and Media Lens, for example) are obviously key to what Chomsky once called “intellectual self-defense.”

And let’s not forget two of the big outlets from which we all need “intellectual self-defense”: The New York Times and the Washington Post. As I write this, a direct search on their sites turns up no mention of the study.

A reprint of a lengthy Reuters article appeared on the New York Times website (6/16/19) with the headline “As Peru Tightens Its Border, Desperate Venezuelans Cling to Asylum Lifeline.” At one point, the article states:

“The crisis has deepened since the United States imposed tough sanctions on the OPEC nation’s oil industry in January in an effort to oust leftist president Maduro in favor of opposition leader Juan Guaidó.”

I guess they forgot to mention that Trump’s sanctions had already been linked to tens of thousands of deaths before he decided to make them more savage in January.

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

Stuxnet's Epic Fail; How the United States and Israel Attacked Iran

Cyber-Terrorism: How the US and Israel Attacked Iran - And Failed

by Maximilian C. Forte - ZeroAnthropology

June 25, 2019

Sabotaging another nation’s power grids, or blowing up industrial plants, are actual acts of war under international law. The term “cyber-terrorism” as used in the title, almost softens the impact of that fact. In recent months and weeks, the US has been active—either by its own account, or according to target nations—in new acts of war that use the digital realm in order to produce concrete effects on the ground.

Venezuela, which suffered debilitating power outages in March, laid at least some of the blame on alleged cyber attacks by the US. The US certainly possesses the means to engage in such cyber-warfare, and has actually done so.

Iran is a case in point. Not only has Iran allegedly been targeted in recent days, it was also targeted by Obama with the aid of Israel. This requires that we review the case of the Stuxnet Worm.

Zero Days (2016)

Why does it matter that we should be aware and informed about the Stuxnet Worm? What is Stuxnet, and what can it do? Who has actually used it, and to what effect? What are the consequences for all of us, now that Stuxnet has been unleashed worldwide?

Americans live under a state which tells them that their country is “the target” of nefarious foreign attackers that engage in cyber-terrorism or other cyber-crimes against the US. They will rarely, if ever, be aware of the fact that it is their own country which has committed the most dangerous and widespread cyber-terrorism—and that as a result, Americans are now vulnerable to the very same computer technologies that their country first deployed against others. This is yet another instance of what others have critiqued as “American innocence”.

Written and directed by Alex Gibney, Zero Days (2016) is a documentary film that runs for just over 113 minutes. The film is briefly described on IMDB as follows: “A documentary focused on Stuxnet, a piece of self-replicating computer malware that the U.S. and Israel unleashed to destroy a key part of an Iranian nuclear facility, and which ultimately spread beyond its intended target”.

Alex Gibney has made several important and well received documentaries, a number of which will be reviewed on this site. He certainly is a prolific filmmaker, focusing on topics that have generated the biggest headlines, or focusing on major personalities. The fact that he is able to churn out such large documentaries in relatively short order (showing that he must be working on another film even before finishing the latest work), is a fact that has attracted some critical commentary, especially when some see work such as Zero Days being little more than a film version of the Wikipedia entry on Stuxnet.

For my part, I am quite sceptical of Gibney’s political aims—at the very least, he is guilty of some hypocrisy.

While Gibney is proud to showcase the fact that he sought out leakers for his Zero Days film, in order to tell us the secrets about Stuxnet, he nonetheless smeared Julian Assange and WikiLeaks for doing the same thing, only better, and on a wider range of topics. We Steal Secrets—a damning title by itself—was one of Gibney’s previous films, which of course won high praise by the media in the US. The fact that NPR has come out and positively publicized Zero Days should be a warning that we view this film with some caution. Otherwise, I will continue to view and review other films by Gibney, just as I do with other filmmakers whose productions deserved criticism.

You can view a trailer for Zero Days below:

The Sheriff is the Outlaw

The film begins with an extract from an Iranian state TV documentary that reenacts the Israeli terrorist assassination of two nuclear scientists in Iran on November 29, 2010. Voice-overs from the mainstream US media refer to the terrorism as “major strategic sabotage”. The film accompanies the Iranian documentary’s action with an Israeli speaker—an anonymous Mossad senior operative—silhouette only, voice distorted electronically, speaking to us from the shadows about the “nature of life” as being one where “evil” and “good” live “side by side”.

He continues by “explaining” that there is an “unbalanced” and “unequivalent” (i.e., asymmetric) conflict between “democracies” that “play by the rules”—the rules shown include the targeted murder of scientists—versus “entities” that “think democracy is a joke”. Presumably terrorism is about making enemies take democracy a little more seriously? In other words, the opening of the film is appropriately sinister, cynical, and menacing.

There is also a certain candour to the film as presented in the words of the Israeli Mossad speaker. There is indeed an asymmetric battle. Had Iran attacked nuclear scientists on the streets of Israel, the Western media would call it a terrorist attack, and Iran would likely be bombed. Instead, Iran is just supposed to absorb Western terrorism, like Americans tolerate rain or a windy afternoon. It is somehow Iran’s natural duty to suffer us.

There is also a candidly twisted interpretation of “the rules”: Western powers get to invent their own special rules, ones that are in direct violation of international law. This is what is actually meant by the “rules-based international order” slogan one hears from the mouths of Western leaders today. The sheriff is the outlaw. The punishment is the crime.

What the anonymous Mossad operative refuses to answer is whether the murder of the Iranian scientists was related to the Stuxnet computer attacks—which are the central focus of this documentary. He is followed by a whole array of experts (one of whom is Gen. Michael Hayden, former CIA and NSA director), each refusing to speak about the Stuxnet Worm, and they all seem visibly uncomfortable just for having been asked. Some explain that it is because it is “classified”. Whomever was behind the Stuxnet attack, they have refused to take official responsibility. However, what is interesting is that these individuals even refuse to simply comment on the press reports of an event that actually happened.

The narrator adds: “Even after the cyber-weapon had penetrated computers all over the world, no one was willing to admit that it was loose, or talk about the dangers it posed”. This film is an attempt to counteract the silence that has been imposed, so that it can be debated publicly.

The question posed by the filmmaker is this: “What was it about the Stuxnet operation that was hiding in plain sight?” And they suggest that maybe there was a way that the computer code could speak for itself.

How Does Stuxnet Work? Who Made It? Who was the Target?

The Stuxnet Worm, which can be delivered by a USB memory stick, is not meant to steal information. It is instead meant to cause industrial systems to malfunction dangerously, while impeding the ability to electronically monitor such systems and to shut them down before a catastrophic event occurs. Stuxnet was used against Iran’s nuclear infrastructure.

The films seeks the insight of experts at Symantec Research Labs in Santa Monica, California (Eric Chien, emergency security response), and at Kaspersky Lab in Moscow, where the filmmaker speaks with Eugene Kaspersky himself. Also at Kaspersky, Vitaly Kamluk explains that there are three principal types of cyber-attackers:

1) “traditional cyber-criminals interested only in illegal profit” looking for “quick and dirty money”;

2) activists, or “hacktivists,” hacking either for the sport of it or to promote a particular political idea; and,

3) nation-states, “interested in high-quality intelligence or sabotage activity”.

Much of the commentary from cyber-security analysts is about the size and nature of the Stuxnet code, and how they collaborated across companies to share the code and their analyses of it. We learn some interesting details here.

Stuxnet first surfaced in Belarus. Sergey Ulasen is interviewed in the film; he was the anti-virus expert who first discovered Stuxnet. Ulasen discovered it when his clients in Iran began to call him in a panic over an epidemic of mysterious computer shutdowns. The malware was first identified on June 17, 2010. What stood out about this code was its “zero days” components.

A “zero day exploit,” as explained by Eric Chien, is simply a piece of computer code that allows it to spread without having to be activated by anyone. One does not need to download an infected file and run it. A zero day exploit is also defined as an exploit that nobody knows about except those who created it—and therefore no patch has been released to counteract it. There are thus “zero days [worth of] protection” against the code.

Stuxnet itself contained four zero days exploits, all by itself, when typically cyber-security might find 12 zero days in an entire year, among millions of viruses. Stuxnet, with so many zero days in it, would probably fetch half a million dollars—and therefore it was unlikely to have been the product of some ordinary criminal gang, but a much more powerful entity. Eugene Kaspersky also discounts the possibility that it was produced by cyber-activists or hacktivists. A consultant in Hamburg came to the conclusion that, given the sophistication of Stuxnet, it had to be the product of at least one nation-state.

Stuxnet’s creators stole its digital certificates from two companies, both in Taipei, and both in extremely close physical proximity to each other, as Eric Chien of Symantec explains. “Human assets” had to be involved—spies—in order to extract the digital certificates, which are guarded behind multiple layers of physical security and not resting on a machine connected to the Internet.

The other significant aspect of the Stuxnet code is that it was designed to specifically target Siemens machinery, but the code analysts were not sure which kind of machinery. Then they discovered that Siemens PLCs (programmable logic controllers) were the intended target. A PLC is typically attached to large pieces of industrial equipment, like valves, pumps, or motors. PLCs are also used to control electrical power plants and power grids.

The next big discovery made by cyber-security analysts was that Stuxnet actively surveyed the systems with which it came into contact, and would run a series of checks to determine whether or not the target PLC has been reached. If it had instead come into contact with some other equipment, it would not activate. The amount of effort put into targeting one specific target, suggested to the analysts that the target had to be mightily significant.

Symantec detected Stuxnet infections across the globe, since it would infect any Windows computers anywhere in the world. Industrial installations across the US itself were/are infected with Stuxnet. Cyber-security specialists were immediately alarmed about the dangerous consequences, where any power system, any industrial production, could be shut down without warning anywhere in the world. However, they soon discovered that Iran was the one country in the world that was most infected with Stuxnet, and this immediately suggested that Iran was the prime target.

To make sense of their findings, the code analysts had to turn to what was making the news, geopolitically. They learned that a number of sensitive oil and gas pipelines coming into and out of Iran were mysteriously exploding. There had also been assassinations of nuclear scientists.

The next advance came in identifying the exact industrial control systems that were being targeted, since the PLC identifier numbers were embedded within Stuxnet’s code. That is when they discovered that the targets were frequency converters from two specific manufacturers, one of which was in Iran. Since the frequency converters were export-controlled by the US nuclear regulatory commission, this told the analysts that the target in Iran was a nuclear facility.

One of the distinctive features of Stuxnet was that it lacked a “call back” component that would enable direct instructions to be given by an operator to the infecting program. Stuxnet was thus fully autonomous. Stuxnet was fashioned to unfold in a facility such as Iran’s Natanz nuclear facility, which is entirely unconnected to the Internet—it is an “air-gapped” facility. However, as no computer system is ever truly and fully air-gapped, as long as new code and new equipment is being introduced, vulnerabilities remain. NSA sources in this film state that the CIA and/or Mossad used “human assets” to infiltrate Natanz. The way that was done was to infect various industrial plants that serviced Natanz, so that contractors would unknowingly carry Stuxnet on a USB key into the facility at some point, to either conduct a software update or introduce new code.

Iranian Nuclear Development

Leaving aside the cyber-security world, the film turns to David Sanger of The New York Times, who was investigating the intersections of cyber-crime, espionage, and nuclear weapons. The emergence of the code alerted Sanger to the fact that an attack was underway. Sanger found Israelis and Americans who were involved in either building a piece of Stuxnet, or who had witnessed its construction—the first big cyber-weapon to be used for offensive purposes. Sanger investigated the history of Iran’s nuclear program, noting that Iran obtained its first nuclear reactor from the US itself, during the reign of the Shah.

For more on the history of Iran’s nuclear development, see:

Sabrina M. Guerrieri, “A War of Words: U.S.-Iran Relations in the Nuclear Debate,” in Maximilian C. Forte (Ed.), Interventionism, Information Warfare, and the Military-Academic Complex (pp. 45-66), Montreal: Alert Press, 2011.

The film then detours into a retelling of the history of Iran’s nuclear development, and its alleged interest in acquiring nuclear weapons. This was a troubling part of the film: given that this film is aimed at Western, primarily American audiences, speaking to them through a language and set of narratives that are familiar to them, Gibney seemed to be framing Iran as a valid target deserving of US aggression. Iran is shown as the potential “danger,” ironic given the history of US interventions and invasions in that part of the world.

Note also that virtually all of Gibney’s “expert” sources on Iran consist of former US intelligence operatives and military officials—we thus hear from Gary Samore, WMD “czar” from 2009 to 2013, and Rolf Mowatt-Larssen, a CIA officer from 1982 to 2005, among others, including Israeli officials. Totally absent from the discussion is anyone in the Iranian government, or anyone in Iran.

The president of the American Iranian Council is interviewed, somewhat mitigating the otherwise complete voicelessness of Iranians. Interestingly, he explains how stringent the International Atomic Energy Agency’s monitoring regime has been, clearly suggesting that Iran was not in violation of its international agreements since it was being thoroughly supervised. He also explained that, under international treaties, Iran has a right to develop nuclear energy. Thus the president of the American Iranian Council ends up being the one moderating voice that offers a little balance in the film, and he is a particularly articulate and intelligent speaker.

However, the problem is not with who supervises the weak, but the fact that no one supervises the strong. The film sometimes seems to miss this basic point, especially by framing Iran as a dangerous nuclear threat.

A Scandinavian former IAEA inspector—who in the film says that he has been to Iran both very few times, and very many times (just one sentence apart)—claims that the agency found residues of weapons-grade uranium (isotope 236), which suggested that Iran had imported it from Pakistan, possibly through the black market.

The one significant observation that arises is that if Iran sought to build nuclear weapons, it was in response to the US invasion of Iraq as part of Operation Desert Storm in 1991. This demonstrated to Iran the extent of the threat posed by the US to even the most formidable militaries of the region, and thus the need for an extra layer of defense.

Iranian fears were further amplified with the direct threats made by George W. Bush from 2002 onward, when he labelled Iran as part of an “axis of evil”. If this argument is correct—the film tends to present speculation from US officials as incontestable fact—then Iran was certainly justified and its response was both reasonable and wise. Indeed, the real mystery is why Iran would not pursue, or is not pursuing nuclear weapons development.

The Cyber Option and Israel’s Role

What led to the deployment of Stuxnet? By 2007/2008, the Bush administration was bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan, and after the WMD fiasco, the film narrative suggests, Bush was not confident about openly challenging Iran over its nuclear program. According to one of the film’s sources, Condoleeza Rice essentially told Bush, “you know, Mr. President, I think you’ve invaded your last Muslim country, even for the best of reasons”.

Bush also did not want to let the Israelis attack Iran, since that would have immediately drawn the US into war with Iran. In fact, as Gen. Michael Hayden attests in the film, Israel lacks the independent capacity to launch and sustain a military attack on Iran without US assistance. General Hayden then adds an astute observation: “there would be many of us in government thinking that the purpose of the raid wasn’t to destroy the Iranian nuclear system, but the purpose of the raid was to put us at war with Iran”.

Another key point made by Hayden in the film is that the Bush administration wanted to avoid a situation where a future president was reduced to one of only two options: either bomb Iran, or Iran developed a nuclear bomb. This seems to be the corner into which Trump is painting himself.

Since the US, under Bush, was not willing to engage Iran in a direct military confrontation, it was the Israeli government under Netanyahu that proposed an alternative means to attacking Iran. A joint group of Israeli and US intelligence officials then advanced the idea to Bush of devising and deploying what came to be known as the Stuxnet worm.

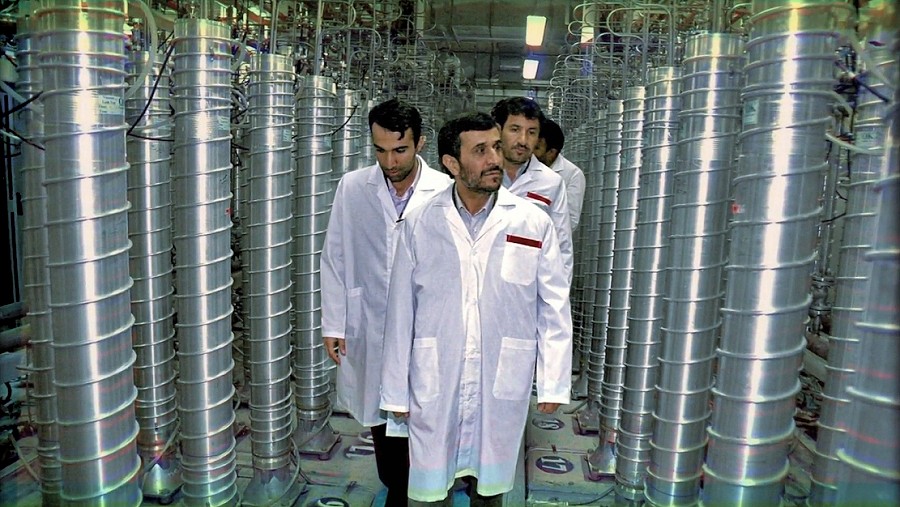

One of the mistakes made by Iran was the publication of a large number of photographs showing Mahmoud Ahmadinejad touring the Natanz nuclear facility, in the company of numerous key scientists—thus inadvertently aiding Israel in its targeting. One of the scientists appearing in a photo, standing behind Ahmadinejad was assassinated a few months later.

Another thing shown by the photos were computer screens displaying arrays of centrifuges that were being monitored. The array of centrifuges showed six groups, each group with 164 items—numbers that perfectly matched what was found in the Stuxnet code. Thus the photos seem likely to have aided the process of devising the attack code.

The Attack

Centrifuges for enriching uranium contain rotors spinning at the speed of sound, with some parts of the centrifuge made of carbon fibres (which shrink with heat), and other parts made of metal (which expand with heat). Maintaining the integrity of a centrifuge is thus delicate and sensitive. Iran’s centrifuges are proudly featured every April for “National Nuclear Day”. The IAEA inspector in the film is particularly impressed with the complexity, professionalism, and sophistication of Iranian facilities. Iran’s centrifuges were specifically targeted by Stuxnet.

How Stuxnet actually operates is graphically demonstrated in the film—and for me, this was the most memorable feature of the documentary. See the extracted clip for a complete demonstration:

The demonstration aside, what Stuxnet was designed to do was sit and wait within the Natanz nuclear facility, and to record and save all operations. Once the required amount of time had passed for the full cascade of centrifuges to be filled with uranium being enriched, Stuxnet would then activate. Its first step was to vastly increase the revolutions of centrifuge rotors to the point that uncontrollable revolutions would rupture the centrifuge. The second step was to block any communication of an emergency to the controllers, by reproducing the old data that it had recorded. The third step was to prevent the controllers from shutting down the centrifuges, by disabling all the kill switches.

The only cyber-security specialists who appears resistant to attributing Stuxnet to the US, is the US-based analyst at Symantec, Eric Chien. He does make the valuable point—one deliberately sidestepped by the US media and US politicians—that attribution is very difficult to make, and the traces that lead back to a supposed origin can be faked. (The assertion made by US intelligence agencies about having evidence suggesting Russian hacking was thus always, at best, highly dubious from the outset.)

The Voice of the Leakers

To ascertain the facts of US and Israeli collaboration in the production and use of Stuxnet, Gibney avails himself of leaks and whistle-blowers in Washington, DC. (It’s only permissible to do so when Gibney does it, unlike his treatment of WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange who did the same.) Gibney comments: “while D.C. is a city of secrets, it is also a city of leaks. They’re as regular as a heartbeat and just as hard to stop”—which again underscores the opportunism of his critique of WikiLeaks in another of his films.

Gibney’s anonymous sources, compiled into one fictionalized character speaking in the film as if she were a hologram, testify that “we” created Stuxnet (“we” was undefined at that point). At the same time—and this strained credulity—these intelligence operatives somehow felt remorse because “we came so fucking close to disaster,” and for some reason, on this subject alone, it is necessary that the intelligence agencies “get the story right” for the public interest. It seemed a like a charming idea: democratic accountability—all of a sudden. It’s possible, but also suggests we interpret their statements with due caution.

Gibney’s sources claim that Stuxnet was the product of a huge “multinational, interagency operation”. The agencies were the CIA, NSA, the Pentagon’s Cyber-Command; in the UK, the GCHQ; “but the main partner” was the Israeli Mossad. The technical work was done by Mossad’s Unit 8200. Now the narrative shifts: “Israel is really the key to the story”. Another source claims that “much of the coding work was done by the [US] National Security Agency and Unit 8200”.

Further bolstering the case against the so-called “Libya model”—ending a nuclear weapons program, disarming, and transferring all materials to the US—this film’s anonymous NSA sources testify to Libya’s centrifuges (P1s) having been studied at Oak Ridge National Laboratory because they were the same kind in use in Iran. Having Libya’s equipment allowed the US to use the items to help engineer Stuxnet, or what the NSA and Cyber-Command called “Olympic Games” or OG. The Israelis aslo did tests using the Libyan P1 centrifuges.

The US: Against International Law

Through espionage, the US also obtained the plans for Iran’s newer centrifuges, the IR2s. In the tests run by the US, they were able to explode the centrifuges by manipulating the rotors. After inviting President Bush to examine shards of the destroyed centrifuges, he reportedly approved the use of Stuxnet. There were no reported concerns expressed by anyone in Bush’s cabinet about the fact that using Stuxnet would constitute an undeclared act of war.

To avoid any legal troubles with the incoming Obama administration, operatives under Bush installed a kill date in the Stuxnet code (January 11, 2009). This was just days before Obama’s inauguration. The desire to bring the operation to a close before Obama’s team took over, is at least tacit recognition of the illegality of the program. Of course, Obama reauthorized the program within his first year in office.

Obama was devoted to cyber-“defense” to protect critical infrastructure in the US—which actually meant he was committed to offensive operations aimed at paralyzing other countries’ critical infrastructure. One can never escape the American international modus operandi of inversion and projection. In fact, the overwhelming majority of cyber-spending under Obama’s budget was devoted to the development of cyber-weapons for offensive purposes.

Under Obama, a whole range of new and powerful cyber-weapons were to be developed. Stuxnet was just the opening shot.

International law, with strict reference

to the use of cyber-weapons, is “written” by custom, as explained by a

US official in the film. Customary law requires a nation-state to at

least say what it did, and why—which the US will not do. Thus the norm

has become: do whatever you can get away with doing. This is a world

which the US has created, as much as it cries innocence today.

Initially, Stuxnet was deemed a success.

Centrifuges did blow up in Iran’s nuclear facilties, a fact verified by

IAEA inspectors. Whole groups of centrifuges were dismantled, and a

number of nuclear scientists were fired. There were other consequences,

as will always be the case, which the US could not control.

Coming Home to Roost

After the attack, Obama only then began

to worry about how Russia and China could do the same to the US, with

the added justification of the precedent set by the US itself. Obama

knew that word would get out eventually, as it did. Nonetheless, Obama

persevered with the program.

Another problem with Stuxnet is that it

was spread all over the world, infecting all sorts of machines, just so

the US and Israel could get at their Iranian targets. The charge made by

NSA sources in the film is that the Israelis took the US code, changed

it, making it much more aggressive, and then launched it without US

agreement. These sources, (feigning?) great indignation at the rude and

inconsiderate Israelis, contradict earlier claims in the film that

Stuxnet was approved for use by both Bush and Obama.

By

spreading far and wide, the Stuxnet code ended up in Russian hands,

where Russian state security experts could study it and potentially use

it, while Iran itself also did the same. Unlike other weapons, when

cyber-weapons are used they can be apprehended intact on the receiving

end.

The Department of Homeland Security, supposedly unaware of what the

NSA and CIA had done, grew alarmed when it encountered the Stuxnet

malware, and its potential to do massively destructive and lethal damage

in the US itself. The DHS Cybersecurity Director, Sean McGurk,

who speaks in this film, was not aware that he was dealing with a

possible case of the chickens coming home to roost.

Likewise, Senator

Joseph Lieberman, on the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

Committee, appears in Senate footage asking—apparently innocently—about

the origins of Stuxnet, and if a nation-state was behind it…not knowing

that it was his own. Of course, what the film does not raise is the

question of whether this was all theatre, to cover for the US violating

international law and engaging in war against Iran.

David Sanger says in the film:

“the United States government has never acknowledged conducting any offensive cyber attack anywhere in the world. But thanks to Mr. Snowden, we know that in 2012 president Obama issued an executive order [Presidential Policy Directive 20] that laid out some of the conditions under which cyber weapons can be used. And interestingly, every use of a cyber weapon requires presidential sign-off”.

Given the extensive over-classification

of information on the US role in producing and using Stuxnet, and the

fact that every US government official interviewed or shown in the film

denied any knowledge of US involvement, no real public discussion can

develop. This in itself does further harm to democracy in the US. Even

the former NSA and CIA director, Gen. Hayden, criticizes

over-classification in his interview for this film.

Rather than invite public debate, the

Obama White House went after the whistle-blowers, going as far as

targeting Gen. James Cartwright, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of

Staff, in a criminal investigation. The US and Israel have yet to

acknowledge the existence of the operation, to this day.

The Failure and the Response

On top of everything else, Stuxnet did not

make a huge impact on the Iranian nuclear program. In fact, the tiny

dip in the number of centrifuges caused by Stuxnet, was counteracted by a

vast and rapid increase in the number of centrifuges installed by Iran,

along with new nuclear facilities. Iran’s nuclear program became even

more advanced, even as it suffered every single known coercive action

thrown at it by the US and its allies, short of direct combat.

The

US is itself highly vulnerable to cyber attacks. US attacks on Iran

encouraged Iranians to form a Cyber Army to fight back. Iran now has one

of the largest cyber-armies in the world, according to the president of

the American Iranian Council. Stuxnet did minimal and temporary damage

to Iran, yet unleashed a wave of responses that showed how use of the

cyber-weapon was a major strategic error.

Iran launched two attacks against the US,

according to Richard Clarke in the film: first, Iran attacked ARAMCO in

Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil company, and they erased all

software, every line of code, from about 30,000 computer devices;

second, Iranians allegedly launched a surge attack on US banks. The

clear message was that, if provoked further, Iran had it within its

means to disrupt the US financial system and the world energy market.

Had Iran not responded, the US apparently

had a much larger plan (“Nitro Zeus”) for total cyberwar against Iran,

which included shutting down its power grids, disrupting military and

civilian communications, and disabling defenses.

Conclusion

There is a great deal of information in

this film that would be interesting to those who are new to geopolitics,

but that is also largely peripheral to the film’s core story. Thus a

lot of time is spent (wasted) on self-flattering operational histories

told by Israeli fighter pilots and US spies, or a New York Times

journalist reciting the most basic essentials of his published stories,

or American government officials presenting their preferred version of

Iranian history. On the whole, the film is about one full hour too long, and it can make for long stretches of tiresome viewing of tendentious material.

This film would be appropriate for

courses in International Relations, Political Science, Middle East

Studies, and any courses dealing with US intervention and/or

cyber-terrorism. Generally, the more critical reviews of this film are

on solid ground, particular those targeting the film’s deficit of any

new information, and the fact that it provides very little that is not

already covered by books, news reports and even Wikipedia.

The visuals

in the film are mostly limited to talking heads, news footage from Iran,

and endless animations of layers of computer code—visually, it is not a

very engaging or memorable film. However, given that the film can

provoke numerous important questions and in some cases provides some

very interesting answers, plus the fact that it effectively condenses

available knowledge, it merits a score of 6.75/10.

(This documentary review forms part of the cyberwar series of reviews on Zero Anthropology. This film was viewed five times before the review was written and published.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)