Remembering G. Simon Harak — a powerful ally of all victims of war

by Philip J. Harak - Waging Nonviolence

November 30, 2019

Co-founder of Voices in the Wilderness, G. Simon Harak was a celebrated teacher, passionate voice for peace and "priest for the people."

On Nov. 3, 2019, G. Simon Harak, a Jesuit priest and passionate advocate for peace and justice, died peacefully in a Jesuit health care facility in Weston, Massachusetts. He had been suffering from a rare form of dementia for several years, with physical effects similar to ALS.

Nominated three times for the Nobel Peace Prize, Simon’s steadfast commitment to recognizing each person’s humanity and dignity made him a powerful ally for all people displaced and devastated by war, wounded by violence of all kinds, and marginalized or ostracized by society.

He and his twin sister, Adele, were born on April 15, 1948 in Derby, Connecticut, though for most of his adult life, Simon would celebrate his Catholic baptism in June as his “true birth date.”

His father, Simon Gabriel, was an immigrant from Lebanon, and was a singer who formed his own orchestra in the big band era and performed on nationwide radio. His mother Laurice, a first-generation Lebanese immigrant, was a professional opera singer in New York City.

It was likely from those artistic performers that Simon inherited his life-long love of teaching, preaching and public speaking. Simon dedicated all of his public and private service to advancing Christ’s nonviolent Kingdom of God, challenging and inviting people to see beyond what is socially constructed, and to decide how to act rightfully and justly.

Simon was a brilliant intellectual, graduating valedictorian from Fairfield University in 1970, majoring in classics. He possessed a reading knowledge of Latin, Greek, French and German. Although accepted into Harvard Law School, Simon answered a deep calling and joined the Jesuits in September 1970. He said that Jesus “called me by name,” and thus began a lifelong companionship with Jesus that became the center of everything he did and said.

During his nine-year preparation for ordination, Simon furthered his formal education, earning a Masters of Divinity from the Jesuit School of Theology in Berkeley, California. But he never let his broad academic accomplishments stop him from ministering to the people. One fall, Simon returned home for a short visit. I noticed that my slightly built brother had developed large forearm muscles. When I asked why his arms looked like that, he told me that he had spent the summer using a chainsaw to help the impoverished people in Appalachia clear trees and build homes.

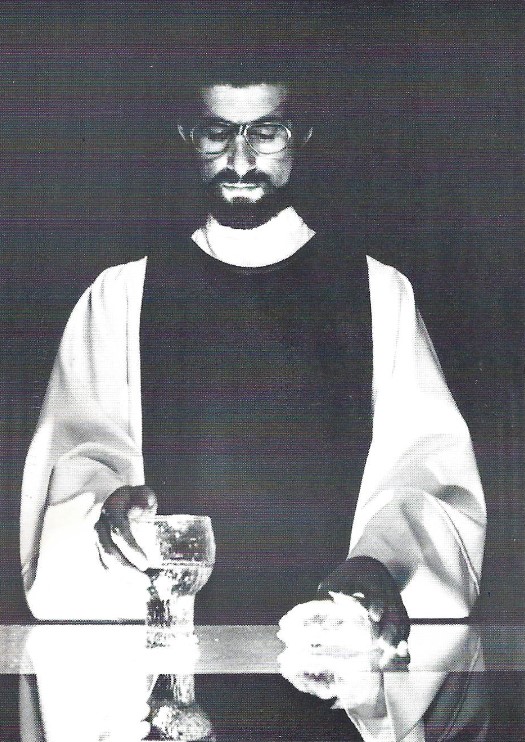

Simon celebrating his first mass as a Jesuit in May 1979.

(WNV/Philip J. Harak)

After his ordination in 1979, he went to Jamaica as a missioner, working as a chaplain with young people. He took the school boys to visits to the public hospital, elderly residences and a home for lepers. Whether individually or as a group, Simon always sought out and ministered to those who were marginalized, suffering and outcast.

Upon his return to the United States, he earned a doctorate in theology and ethics from Notre Dame in 1986. He crafted his dissertation into his first book, “Virtuous Passions: The Formation of Christian Character.” Preeminent theologian Stanley Hauerwas called Simon’s work “stunning,” and wrote that “he is able to write about Aquinas on the passions making that text come alive in a way that no one else has been able to do.”

Simon often said that he loved to share knowledge and to incite people to think critically for themselves. Teaching and lecturing were lifelong passions. Accordingly, he became a beloved, life-changing teacher and award-winning professor of religion and Christian ethics at Fairfield University from 1986 to 2000. While there, his focus on justice and peace was both local and global. For example, he and his students became involved in protests for equitable salaries for dining hall workers (to the chagrin of most in the administration).

In the fall of 1995, he embarked on a cause that intentionally put him and his fellow activists in violation of both U.S. State Department policy and the U.S. Constitution’s forbiddance of aiding and abetting the enemy. Then, the Iraqi people were the “enemy,” and they suffered terribly from U.S.-imposed sanctions, especially the children. With about 250 children under the age of five dying daily since the inception of the sanctions regime in 1990, former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clarke described the situation as genocide against the Iraqis. Always committed to deep research, which he said would lead to facts, and then to truth, Simon felt an irresistible movement to act on behalf of the Iraqis.

Along with Kathy Kelly, Simon started a humanitarian organization called Voices in the Wilderness, which is now called Voices for Creative Nonviolence. Simon traveled to Iraq three times, ministering to the children and people there. Their delegations brought much-needed food, medicines, clean water, and even toys to the children and people in need.

“Without Simon, I wonder if Voices in the Wilderness would ever have been initiated,” Kathy recently said.

“Simon’s guidance, energy, scholarship and kindness greatly helped Voices send 70 delegations to Iraq, all in open and public defiance of the U.S./U.N. economic sanctions against Iraq. Whether leading delegations to Iraq, organizing local actions, joining in lengthy fasts, or making presentations, Simon always made time for Voices in the Wilderness.”

All throughout his life, Simon balanced his academic pursuits with his calling to be a “priest for the people.” He loved his service as a pastoral priest, and he would often fill in for missing or vacationing parish priests across the country. He was proud of the successful marriages of more than 30 couples for whom he prepared and performed marriages, including my own marriage to Margaret Savage, in 1995. He was always available to minister to the sick, the grieving, and to the poor who approached him on the street. He was also just a good friend, always sending postcards from wherever he was in the world, and bringing home thoughtful little gifts.

“As a Christian commanded by my Master to love my enemies, I have yet to find a way to do that while preparing to, and then, killing them!” - G. Simon Harak

Witnessing endless unspeakable suffering and pain on his last visit to Iraq seemed to galvanize Simon away from his full professorship. He decided he needed to be a full-time voice for all the victims of war, including the warriors themselves. He wanted to awaken people from the stupor of blind acceptance of warfare, and expose the real human costs of war. Using his skill for discovering hidden facts, and for expressing complex issues clearly, Simon worked diligently at the War Resisters League in New York City as the national anti-militarism coordinator, from 2003 until 2006.

Late in 2005, financial benefactors Terry and Sally Rynne, along with the Jesuits at Marquette University, invited Simon to found and head the Marquette University Center for Peacemaking. Students there created local and national outreach programs, focusing on teaching nonviolent conflict resolution in schools and communities. The center sponsored two national conferences and the publication of an academic journal. Simon shepherded that center until 2013, when his illness forced his resignation and his return to the Campion Health Center in Weston, Massachusetts. Even while the illness was robbing him of his mental and physical abilities, he continued to serve residents and staff there as long as he was able.

Simon leaves a legacy as a passionate disciple of the nonviolent Christ, performing his mission until his last breath. He had made over 2,000 television, radio and speaking engagements at venues in the United States and abroad regarding truths and human costs of the Iraqi war, and later, about war profiteering. While he was gifted in creating nonviolent actions and in intellectually dismantling the maddeningly tautological and false promises of violence, he did not see nonviolent strategies merely as an end in themselves, but as constitutive to Christian discipleship. He understood Jesus’ way to be based upon what Jesus clearly did and said: endless forgiveness, compassion, mercy and nonviolent love of friends and enemies, with no exceptions.

Possessing a sharp wit within a great sense of humor, Simon would sardonically comment, “As a Christian commanded by my Master to love my enemies, I have yet to find a way to do that while preparing to, and then, killing them!” Often at odds with “just warrior” advocates both within his own order and broadly inside and outside of Christianity, Simon would remind those advocates that “just war theory” was never taught by Jesus.

He would always correct the common misunderstanding that nonviolence meant non-resistance or passivity. He would provide examples and also personally act in ways consistent with those other nonviolent resisters, both famous and ordinary, who believed and acted with “a force more powerful” than violence. He challenged the pillars of governmental, institutional and personal violence, and sought to liberate people by presenting meticulously researched information that countered the narratives purported by a culture inured in the myths of redemption or lasting safety through revenge, oppression and violence.

Simon loved life, and would balance his hours of research and writing, his pastoral ministry and full immersions into human suffering, with many different activities he found both revitalizing and fun. He would begin each day with private prayer with Jesus, followed by his joyful celebration of the Mass. He loved music and theater, and would thoroughly enjoy taking friends and family to concerts, plays, museums and movies. He read about two or three science fiction books per week. A lifetime baseball fan, we would attend games everywhere he was stationed.

His Jesuit funeral on Nov. 8 at the Weston Chapel was a beautiful and moving ceremony. It was the culmination of incredibly respectful, medically sensitive and loving treatment he always received there, from his Jesuit brothers and all the staff.

Simon leaves a loving and eternally grateful group of family and friends. His father, Simon, died in 1970, three weeks after his son joined the Jesuit Order. His mother, Laurice, died in 1992. Along with his sister Adele Campbell, he leaves his sister Laurice Boutagy, and his two younger brothers — me and John — his siblings’ spouses and their children.

When Simon left home in 1970, I felt a deep sadness. Employing his remarkable gift of witnessing and validating other’s emotions, he consoled me by explaining that, “I have to leave you and this family, Philip, in order to best serve Jesus. A true test of my Christianity is to treat everyone else in the world with the same kind of love I have for you and the family.” “Blessed be Simon,” James Douglass wrote upon hearing of his friend’s passing, “who has walked with us all in so many ways … and will continue to do so.” Amen, Jim.

Philip J. Harak Ed.D., is a retired public high school English teacher and varsity baseball coach. He heads Socially Just Community Development, LLC, and recently completed the forthcoming book based on 36 of his brother Simon’s homilies, titled, "In the Company of Jesus: Using a Jesuit and His Brother’s Scriptural Reflections on Jesus’ Original Teachings to Deepen your Journey with Jesus Today."

No comments:

Post a Comment