LITTLE BOY & FAT MAN – THE TWO INFO-WAR BOMBS DROPPED ON RUSSIA

by John Helmer - Dances with Bears

@bears_withThe London Charter of 1945, creating the legal basis for the Nuremberg prosecutions, introduced a special provision, Article 9, to turn individual associations of Germans into “criminal organisations”.

But when the doctrine is advocated in media reports and books about Russia and the Russians running the country since 2000, the doctrine isn’t a hate crime. It’s a war weapon whose detonators are being primed every day. The second handbook for demonstrating how to clean, load, and fire this weapon against Russia was published last year by Catherine Belton (lead image, right). She and Rupert Murdoch’s publishing house HarperCollins call their Russia war-fighting manual Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia, and Then Took on the West. Belton, HarperCollins and the book are now on trial for lying and libel in the High Court in London.

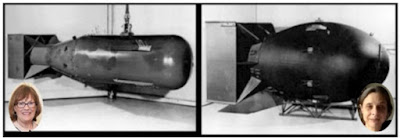

In operational terms for the Russia war-fighters, Belton’s book was Fat Man, nickname for the US atomic bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki. Little Boy, the US bomb dropped on Hiroshima, came first. Before Belton, that was Karen Dawisha’s (left) book called Putin’s Kleptocracy, Who Owns Russia, published in 2014 by Simon & Schuster. Belton doesn’t mention Dawisha’s name or give her the credit for publishing the first manual in the info-war series.

Dawisha makes Gennady Timchenko the lynchpin of her case that President Vladimir Putin has enriched his friends and cronies from St. Petersburg; that they in turn have enriched him corruptly; and that together, they make a criminal organisation to be prosecuted, convicted and punished by the US Government and its allies.

Dawisha was writing before the Ukraine putsch of February 2014 and the NATO sanctions war which started against Russia the following month. At the time, Timchenko owned Gunvor, a trader of Russian oil based in Geneva. He also had control stakes in rail, port and pipeline transportation of oil, and the ambition to take over Sovcomflot, the state-owned oil and gas tanker fleet.

Timchenko was Putin Crony Number One in Dawisha’s manual. Her target was their links and their association. But Dawisha attempted no analysis of Timchenko’s business – or of any Russian commercial business or state enterprise except for Gazprom, the state gas producer. Her account of that was entirely based on allegations by William Browder; Dawisha reported none of the Russian or American investigations of Browder’s fabrications.

William Browder (left) and Karen Dawisha exchange book-sale promotions.

Dawisha’s sources for the Timchenko story were reporters for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times, each of them partisans of Mikhail Khodorkovsky and other Russian business rivals of Timchenko. Dawisha was partisan herself. “Only slowly did Putin’s malevolence dawn on Western governments, “ she wrote about the Russian oil business, “especially in light of the Kremlin’s transparently predatory actions in taking apart Russia’s largest private oil company, Yukos, and imprisoning its independently minded owner, Mikhayl Khodorkovskiy, in 2005”.

The relationship between Timchenko and Putin began in the St. Petersburg city government in 1991, Dawisha claimed, when “Putin’s very first application to export materials was with Kirishinefteorgsintez, signed on December 20, 1991, citing authorisation from Deputy Prime Minister Gaidar on December 4, 1991.”

Gennady Timchenko in Leningrad in 1979; with President Putin in

St. Petersburg, June 2017. For the archive on Timchenko’s businesses, click to read. In 2009 Timchenko issued this threat to sue Russian media for reporting on his businesses.

“Secretly”, Dawisha wrote, claiming to know the secret, Timchenko had given Putin “a 75% stake in the Gunvor oil trading firm and had amassed thereby a fortune of $40 billion”. The evidence for that, according to Dawisha, amounted to media reports which “did not produce concrete evidence of that ownership. Then on March 20, 2014, a U.S. government sanctions announcement claimed there was a direct connection between Putin, Timchenko, and Gunvor: ‘Timchenko’s activities in the energy sector have been directly linked to Putin. Putin has investments in Gunvor and may have access to Gunvor funds.’ ”

For Dawisha, the US Treasury press release was proof – “their reported subsequent association in the oil trading company Gunvor, which was confirmed by the U.S. Treasury in announcing sanctions against Timchenko.” That the Treasury’s charge depended for its veracity on the earlier press reports, and that they depended on anonymous US government official briefings, was a circularity which did not disturb Dawisha, if she noticed it.

This circularity is all there was; that is how the chain reaction info-war bomb is fabricated.

Source: US Treasury, March 20, 2014

“In this book”, Dawisha began, “I lay out the case for the existence of a cabal to establish a regime that would control privatisation, restrict democracy, and return Russia to Great Power (if not superpower) status. I also detail the Putin circle’s use of public positions for personal gain even before Putin became president in 2000.” “I conclude that from the beginning Putin and his circle sought to create an authoritarian regime ruled by a close-knit cabal with embedded interests, plans, and capabilities, who used democracy for decoration rather than direction.” “The book has shown that the group now in power started out with Putin from the beginning. They are committed to a life of looting without parallel. This kleptocracy is abhorrent not just because of the gap between rich and poor that it has created, but because in order to achieve success this cabal has had to destroy any possibility of freedom.”

Dawisha acknowledged she had taken the term “cabal” from testimony given to a congressional committee in 1999 by a former CIA official who was station chief in Moscow between 1992 and 1994. After “retirement” from the Agency, he told the committee, he had worked as a security consultant for an oligarch’s bank. That was the witness testimony of Richard Palmer before the House Committee on Banking and Financial Services in September 1999.

In the résumé he still circulates to sell his consulting services, Palmer

describes

that before he was promoted to Moscow station chief he was a

clandestine operations base chief in the Soviet Union, and was awarded

the Agency’s certificate for “exceptional intelligence collector” of the

year, 1985 and 1990. Palmer doesn’t speak or read Russian.

Palmer also told the congressmen that after retiring officially from the CIA he had “worked for three years in the FSU [Former Soviet Union] as a business and security consultant, as well as working as the director of training within one Russian based bank. As a result, I have experience based upon direct contact with FSU security and police services, as well as members of Russian banking, business, Organized Crime and corrupt officials.” Palmer didn’t name the Russian bank which agreed to employ the CIA agent; it was Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s Menatep.

Cabals can be obscure to some, but they can’t be a secret to all. Dawisha claimed to have identified almost every connexion which cabal members Putin and Timchenko had tried to conceal from their beginnings in the Soviet KGB in the 1980s to their business ventures in St. Petersburg in the following decade, and then to their oligarch schemes after Putin became president in 2000. But the outcomes of their plotting cannot be secret – not if up to $40 billion has been accumulated, allegedly, as one of the individual stakes.

The financial results must be obvious for Dawisha’s picture to be credible. For the cabal to be true in general, the particulars in the Sovcomflot case ought to be visible evidence for it.

Sovcomflot, the state shipping company on whose privatisation Timchenko had designs, has provided unique evidence because it’s the only one for which the English courts – three courts; seventy-six days of courtroom trial; thirteen judges; thirteen years of evidence-gathering, testing, review and appeal – have inspected every allegation of cabals, cronies, corruption, and crime, and rendered explicit judgements about how Russian state enterprises, patronised by high state officials up to the prime ministry and presidency, have actually operated.

Read the Sovcomflot dossier here.

Prime Minister, then President Dmitry Medvedev was never mentioned in the Sovcomflot court evidence or verdicts. Putin, however, appears several times, always in cabal company. Justice Andrew Smith’s main judgement, for example, reported in December 2010 that “according to Mr. Nikitin, around this time Mr. Timchenko established good relations with Mr. Vladimir Putin, who was then the deputy mayor of St Petersburg and who was, of course, to become the President of the Russian Federation and is its Prime Minister. Mr. Putin’s deputy was then Mr. Igor Sechin, who was Deputy Chief of the Russian Presidential Administration while Mr. Putin was President and is now [December 2010] First Deputy Prime Minister.” — Para 184.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

Source: http://www.bailii.org/

Yury Nikitin’s testimony in the High Court was also that “Mr. Timchenko believ[ed] that, because he enjoyed a good relationship with President Putin, he did not need to include Mr. Malov and Mr. Katkov in his new enterprises, including the business of Gunvor International which he set up in 2002.” — Para 190.

This was a fundamental element of the case which the three defendants in Sovcomflot’s case presented to the court in their defence — Dmitry Skarga, former chief executive of Sovcomflot; Tagir Izmailov, former chief executive of Novoship before it was taken over by Sovcomflot; and Yury Nikitin, Sovcomflot’s tanker chartering partner. Skarga had been appointed by Putin and had enjoyed the confidence as well of Timchenko and of Nikitin, who had been by his own testimony a founding shareholder in Gunvor from 1999. Between 2002 and 2004, when Putin was already well established in the Kremlin, Gunvor was one of Sovcomflot’s oil cargo clients. If Skarga reporting regularly to Putin and to Timchenko, and if Nikitin chartering with Gunvor and Sovcomflot had believed Putin was a concealed shareholder of Gunvor, or of Surgutneftegas and the Kirishi group of companies which appear in Dawisha’s story of Putin’s “interlocking network of associations”, they would have said so in their court testimony. But they didn’t.

Instead, decided Justice Smith in a judgement confirmed on repeated appeals: “according to Mr. Nikitin, after the Fiona [Sovcomflot] action had been brought he heard ‘from sources whom I cannot name (for fear of their safety)’ that Mr. Timchenko, together with Mr. Frank [Sovcomflot chief executive Sergei Frank] and Mr. Sechin, was ‘behind the criminal and civil action being taken against me’. He and Mr. Skarga submitted that the Fiona actions against them, like the criminal proceedings, have been brought because of Mr. Nikitin’s dispute with Mr. Timchenko and Mr. Skarga’s dispute with Mr. Frank. They said that, even before Mr. Skarga had left Sovcomflot, moves had been made to undermine their positions and to compromise them. They gave evidence that on 22 July 2004 the police conducted armed raids on the offices of Henriot [a Nikitin company] in St Petersburg, of Sovcomflot in Moscow and of NSC [Novoship] in Novorossiysk, and Mr. Skarga’s evidence was that, when a few days later he spoke to Mr. Frank about the raids, Mr. Frank obviously knew about them. They maintained that Mr. Katkov and Mr. Malov have not been the target of proceedings, despite them having an interest in some of the transactions of which the claimants complain, because Mr. Frank is on friendly terms with them as well as with Mr. Timchenko. (Mr. Smirnov, who also had some involvement in Mr. Nikitin’s business ventures, died in 2004 before these proceedings were brought.)”

Left to right: Dmitry Skarga, President Putin, Tagir Izmailov, meeting at the Kremlin in November 2002.

From less evidence, none of it from a direct participant, eyewitness, or document, Dawisha concluded that at the heart of the St. Petersburg cabal, Putin displayed a “pattern of uncontrollable greed, of wanting what rightfully belongs to others, which… has resulted in over twenty official residences, fifty-eight planes, and four yachts. Sadly for Russians, Putin does not ‘own’ any of these, except his St. Petersburg properties and perhaps his first yacht, the Olympia, which was presented to him as a gift by a group of oligarchs headed by Roman Abramovich just prior to Putin’s becoming president in 2000 and delivered in 2002”.

Again, the cabal of cronies: “The capture of the state and its financial reserves by the cronies around Putin has been a distinguishing feature of his entire rule. In this kleptocracy, the state nationalises the risk but privatises the reward. Access to this closed group required loyalty, discipline, and silence. Once within the group, officials could maraud the economy with impunity. Key to its successful functioning over time has been the unity of the key officials and their willingness to allow Putin to be the ultimate arbiter of any disputes, without using (and indeed undermining) the written law.”

Dawisha admitted she lacked direct evidence but claimed she had an alibi: “when the subject of study is how, when, and why Russian elites decided to take the country away from democracy, obviously no one from this group is giving public interviews, and if they do, as happened with Aleksandr Litvinenko, they suffer a cruel death.”

There’s one exception – Dawisha reported from an interview Boris Berezovsky gave her in February 2000, after he had fled to London and begun his campaign to overthrow Putin; and from excerpts of testimony ten years later in Berezovsky’s London High Court case against Abramovich. Berezovsky was the only Russian business figure to whom Dawisha spoke. “I spent almost eight years studying archival sources, the accounts of Russian insiders, the results of investigative journalism in the United States, Britain, Germany, Finland, France, and Italy, and all of this was backed by extensive interviews with Western officials who served in Moscow and St. Petersburg and were consulted on background… I also consulted with and used many accounts by opposition figures, Russian analysts, and exiled figures who used to be part of the Kremlin elite.”

Dawisha’s reliance on Berezovsky was not inhibited by his record for dishonesty. Between October 2011 and January 2012 over 34 days of trial hearings – less than half the time taken in the Sovcomflot trial – Berezovsky, Abramovich, and a line of powerful Russian businessmen testified to their relationships with the Kremlin, their business practices, written and oral agreements, and the division of several billion dollars’ worth of assets, principally the oil company Sibneft (before it merged with Yukos) and the Russian Aluminium company (Rusal). In all, Berezovsky claimed Abramovich had caused him losses of between $5 billion and $6 billion.

Justice Dame Elizabeth Gloster issued her judgement on August 31, 2012.

Left: High Court Justice Dame Elizabeth Gloster. Right: Boris

Berezovsky, photographed at home in 2012, following Gloster’s verdict

against him but before his suicide death on March 23, 2013.

“Every, or almost every, aspect of the alleged agreements was in dispute. Significantly there were no contemporaneous notes, memoranda or other documents recording the making of these alleged agreements or referring to their terms… Because of the nature of the factual issues, the case was one where, in the ultimate analysis, the court had to decide whether to believe Mr. Berezovsky or Mr. Abramovich. It was not the type of case where the court was able to accept one party’s evidence in relation to one set of issues and the other party’s evidence in relation to another set of issues.”

Gloster decided for Abramovich; Berezovsky, she concluded, was a liar.

“On my analysis of the entirety of the evidence, I found Mr. Berezovsky an unimpressive, and inherently unreliable, witness, who regarded truth as a transitory, flexible concept, which could be moulded to suit his current purposes. At times the evidence which he gave was deliberately dishonest; sometimes he was clearly making his evidence up as he went along in response to the perceived difficulty in answering the questions in a manner consistent with his case; at other times, I gained the impression that he was not necessarily being deliberately dishonest, but had deluded himself into believing his own version of events… I regret to say that the bottom line of my analysis of Mr. Berezovsky’s credibility is that he would have said almost anything to support his case.”

Gloster’s ruling runs for 1,253 paragraphs, with an appendix and 555 reference notes; her executive summary issued simultaneously, for 96 paragraphs over 38 pages. Dawisha didn’t read a word.

Instead, Dawisha cited the transcript of two days of the court hearings on November 7 and 8, 2011. Over the two years which elapsed after the case ended, and a year after Berezovsky’s suicide, Dawisha had not consulted anyone involved in the case; the transcript she used came from the Moscow legal website, Pravo.ru. But Dawisha’s judgement was the opposite of Gloster’s – everything Dawisha quoted Berezovsky as saying was the truth, she insisted, especially about Putin.

“The president said that he would bash my head with a cudgel,” Berezovsky told Dawisha to report in her book. “The cudgel turned out to be too short; he cannot reach me here [London]. So he started hitting people close to me. In other words, it is in the very worst tradition: blackmailing someone by putting pressure on their relatives, their associates, their friends.”

Although there have been a great many court decisions in the international courts in which the direct testimony of Russian oligarchs and politicians has been tested against media reporting, spy stories, and US Government documents, Dawisha ignored almost all of them in her book. In 217 pages of Dawisha’s footnotes there is just one reference to a US court case – a diamond embezzlement scheme of 1994-96 involving then-President Boris Yeltsin, his family and Moscow officials unconnected to Putin and his associates.

Dawisha’s references to a Swedish tribunal case and two cases at the European Court of Human Rights aren’t evidence of the cabal. She also reported references to a Spanish magistrate’s investigation of Russian mafia dealings in Spain, but that did not reach court because the case was dropped for lack of evidence; Dawisha believed the allegations to be true because a State Department cable from the US Embassy in Madrid claimed so; and because NATO intelligence agency sources leaked a variety of allegations to the Spanish media; one of them was the claim that Berezovsky had entertained Putin at a Spanish villa several times during 1999.

Dawisha not only refused to investigate courtroom tests of the evidence she accepted from journalists. She also refused to submit to the truth test of the English courts for her own book. In the story she told, her manuscript was reviewed by Dawisha’s regular publisher, Cambridge University Press (CUP), but it was rejected by the publisher’s lawyers on the ground that the evidence for her allegations against individuals would not, or might not, stand up under cross-examination and satisfy the truth defence in law.

That’s not how Dawisha reported what had happened to the truth.

Instead, she and her book had been victimised, she claimed, by another cabal — “the rich and the corrupt from many different countries [who] use U.K. courts for libel tourism as a way of suppressing investigative work into their worlds. Some authors walk away and find another publisher. Others have gone ahead with publication in the U.K. and then have had to face a court case and the ultimate pulping of their books, sometimes over a single paragraph. I have never blamed CUP, with whom I have had a long relationship, for their decision, and the fact that Simon & Schuster also has decided not to publish this book in the U.K. underscores that the problem lies with U.K. libel laws, not with CUP.”

Alice Mayhew, Dawisha’s editor at Simon & Schuster in New York, had been taking editorial advice from the CIA since James Jesus Angleton ran the CIA’s counter-intelligence operations against suspected Russian moles. Also, Simon & Schuster’s lawyers advised that Dawisha’s book was covered by New York state and federal US statutes protecting American authors and their US publishers from libel judgements issued against them in a British or any foreign court. Simon & Schuster knew it; Dawisha pretended not to.

There was a moment during the Berezovsky-Abramovich trial when the veracity on Russian affairs of journalists, academics, government officials, and also the oligarchs themselves, was debated in court by two academic historians of modern Russia. One hired by Berezovsky, one by Abramovich, provided reports in preliminary evidence; they then testified on oath and under cross-examination for their expert opinions on what had happened to keep President Yeltsin and his cronies in power. The historian witnesses disagreed with one another sharply.

Oxford University historian Robert Service attacked Stephen Fortescue, an Australian academic, for depending on stories he had clipped from the Russian press rather than on direct participant accounts or financial evidence of the type of transactions Berezovsky and Abramovich conducted with each other. Here is Service’s courtroom testimony on December 2, 2011.

“SERVICE: My position is that we do not know the precise details of the business transactions that we’re talking about here.

MRS JUSTICE GLOSTER: That’s your main point?

SERVICE: That is my main basic point, and that these general statements about what actually happened in each of the loans-for-share deals aren’t yet convincing because what documentation is available is too slim.”

According to Service, “I’m asked to give evidence here as a historian, I don’t accept anybody’s word, just because they say that something happened, without the kind of evidence to back it that does not come from the person who is saying it. So there has to be a sort of — in a perfect world, there has to be a multiplicity of sources to corroborate anything as having happened or not having happened… I would just add the reservation that the statements by big businessmen in Russia in the 1990s about what they did or did not do are riddled with cases of falsification, obfuscation and the rest of it. One has to be very, very careful about accepting anything from any of them.” The evidence for the business history of Russia in the 1990s, he concluded, “is just not in yet.”

For more on Service’s record as a Russian war-fighter himself, read this.

In time – the historian was telling the judge – the truth of the matter might become clear. But not then. What is certain, Service testified, was that reporters of the time, Russian and western, media or state employed, cannot be reliable sources. So anyone relying on them for an account of how Russia was ruled in those days was certain to make mistakes. Not necessarily political mistakes, but worse – mistakes of fact, mistakes of truth.

The judge said she wasn’t obliged to decide this. “Given the substantial resources of the parties, and the serious allegations of dishonesty, the case was heavily lawyered on both sides. That meant that no evidential stone was left unturned, unaddressed or unpolished. Those features, not surprisingly, resulted in shifts or changes in the parties’ evidence or cases, as the lawyers microscopically examined each aspect of the evidence and acquired a greater in-depth understanding of the facts. It also led to some scepticism on the court’s part as to whether the lengthy witness statements reflected more the industrious work product of the lawyers, than the actual evidence of the witnesses.” – Para 29.

After such painstaking examination, the judge said her task was to decide between Berezovsky and Abramovich according to the criterion required by English trial law – the burden of proof. “The burden of proof,” ruled Gloster, “was on Mr. Berezovsky to establish his claims. As the only witness, on his side, who could give direct oral evidence of the making of the alleged agreements or the alleged threats, the evidential burden on him was substantial. Ultimately, it was for Mr. Berezovsky to convince the court, on the balance of probabilities, that the alleged oral agreements and threats had indeed been made, not for Mr. Abramovich to convince the court otherwise… [T]his case fell to be decided almost exclusively on the facts; very few issues of law were involved. Because of the nature of the factual issues, the case was one where, in the ultimate analysis, the court had to decide whether to believe Mr. Berezovsky or Mr. Abramovich. It was not the type of case where the court was able to accept one party’s evidence in relation to one set of issues and the other party’s evidence in relation to another set of issues.” — Para 32.

Gloster, having weighed the scales of probability, decided they tipped decisively against Berezovsky.

“To Free Russian Journalism” – Dawisha’s dedication at the start of her book tipped her scales in favour of sources which do not meet the burden of proof. The rest of Dawisha’s case against Putin and his cabal followed for the purpose, she declared for herself, of justifying, encouraging and expanding the US war for regime change in the Kremlin. Dawisha advocated her not-so-tacit recommendation for US force against Putin and his cronies because “Putin will not go gentle into the night.”

Putin is “the ultimate arbiter”; boss of a “protection racket dependent on a code of behaviour that severely punishes disloyalty while allowing economic depredation on a world-historic scale for the inner core of his elite”; “not the leading figure from the beginning [b]ut he created an interlocking web of personal connections in which he was the lynchpin. He wasn’t the only strong person in these groups, but he was the only one who stood astride all of them. And they would be allowed to make money and come to power with him, and only because of him.”

This is how info-war bombs against Russia work. They have been made to detonate and destroy, not only the Russian targets, but also the requirement for evidence of court standard against them.

No comments:

Post a Comment