THE THUCYDIDES CLAPTRAP – RUSSIAN LESSONS AT THE PEAK OF THE PANDEMIC, AND JUST AFTER

by John Helmer, Moscow

@bears_withMay 14, 2020

Cardiology doesn’t expire when people die of heart attacks. Just so, no one should expect that when a man dies of the corona virus, or hundreds or thousands of men, the sociology of their pre-existing health, race, ethnicity, income, education, ideology – in short, their class in the old- fashioned meaning of the word — goes belly up at the same time. For understanding and prediction, sociology will always trump epidemiology — the basic reproductive ratio R0 of Covid-19 might run from 3 to 9, but the R0 of class struggle is many times more virulent.

Thucydides’ chapter on the plague of Athens appears in Book II of his History of the Peloponnesian War. It’s very short – just nine sections covering in the English translation less than five pages. Exactly why Thucydides popped it into his history at all is far from clear because, notwithstanding the heavy death toll, he doesn’t claim it made a significant difference to Athenian policy or to the outcome of the war with Sparta.It is therefore surprising that so many pundits, even the Russia-hate specialist Anne Applebaum, think to publish an interpretation of the sociology of the plague of ancient Athens, circa 430 BC; and taking Thucydides as their source, give lectures on how much the European and American societies can learn from him on Covid-19, but have failed to learn to date. At the same time as they depend on Thucydides for their lessons, they ignore the very first of his – that was his dismissal of the source and cause of the plague among the foreign enemies of the ancient Athenians. In other words, Thucydides wouldn’t be blaming China and Russia for Covid-19 now any more than he blamed the Spartans then.

Because Thucydides himself contracted the disease and recovered from it, he concentrates half his tale on describing the symptoms. These are so precise, they have led modern medical scientists to diagnose what the disease was, and rule out what it wasn’t. Recovery of DNA from the grave bones of the time isn’t conclusive. Neither are diagnoses ranging from measles to glanders, typhus, smallpox, lassa fever, toxins in wheat.

At the start of the plague, which lasted in diminishing waves for almost five years, 430 to 425 BC, the population of Athens was about 300,000, not counting slaves; about 400,000 in total.

Today that’s the size of New Orleans or Tulsa or Tampa in the US. In plague terms they aren’t similar to each other. The variation in their case infection and death rates from Covid-19 is large: in New Orleans there is 1 case in 58 people; in Tulsa 1 in 17,372; in Tampa, 1 in 923. Deaths as a proportion of cases has been above 7% in New Orleans; 5% in Tulsa; 3% in Tampa. For the epidemiological picture across the US, click to read this map.

It’s too early for the sociology to become reliable, but not too soon for one correlation to be obvious. The poorer and blacker the town, the higher the infectiousness and case numbers. Related to this, the worse the public health facilities available to treat infections, the higher the death rates. By comparison, the biggest of the cities, New York, is reporting a case rate of 1 in 44 and a death rate of 10% — the worst plague outcome in the country.

The outcome for ancient Athens was worse. By the end of its plague, about 100,000 had died – 1 case in 3 or 4 people. Lockdown within the city walls was an accompanying military requirement because of the advancing Spartan army; quarantine by viral hotspot was a measure adopted inside the city, though there was no social distancing, no masks, gloves or disinfection. Recent evidence from a mass burial site in Athens reveals no conclusive evidence of the medical cause, but considerable evidence for the dumping of bodies. Thucydides explained that was a result of the suddenness of the fatalities, the lack of income for “the necessary means of burial”, and the collapse of “every rule of religion or law”.

In Thucydides’ sociology, the plague started across the Mediterranean in Ethiopia and Upper Egypt; spread by ship, trade and travel, arriving first in the port of Piraeus, and thence to Athens. Bio-warfare was initially suspected, as it is now by President Donald Trump, his re-election allies, and the Australian government. Because “there were no wells [in Piraeus] at that time, it was supposed by them that the Peloponnesians had poisoned the reservoirs.” Fake news, Thucydides was sure of it.

Once in Athens, medical pre-conditions and age were ruled out.

“That year, as is generally admitted, was particularly free from all other kinds of illness…People in perfect health suddenly began to have burning feelings in the head… Those with naturally strong constitutions were no better able than the weak to resist the disease, which carried away all alike, even those who were treated and dieted with the greatest care.”

That last line allows the idea that to Thucydides the Athens plague was classless in its infectiousness and lethality.

The sociological result, he emphasized, was the breakdown of social values, law, order, and deterrence into

“a state of unprecedented lawlessness. Seeing how quick and abrupt were the changes of fortune which came to the rich who suddenly died and to those who were previously penniless but now inherited their wealth, people now began openly to venture on acts of self-indulgence…to spend their money quickly and to spend it on pleasure… As for what is called honour, no one showed himself willing to abide by its laws…No fear of god or of law of man had a restraining influence…As for offences against human law, no one expected to live long enough to be brought to trial and punished.”

What’s not said by Thucydides (possibly because he didn’t see it) was mass rioting for food in the poor quarters, looting of shops, home invasions, street robbery and murder in the rich ones. The comparable US data on the same measures of criminality in New Orleans and New York City aren’t available, but so far the American evidence looks to be the same as for ancient Athens.

Thucydides added some final sociology on the impact of media, religion, science.

“The doctors were quite incapable of treating the disease because of their ignorance of the right methods.” Thucydides was implying there was a “right method”.

But he dismissed “prayers made in the temples, consultation of oracles”, social communication among friends and family.

“Nor was any other human art or science of any help at all”.

Why Thucydides decided to report the plague is far from clear, since he didn’t think it made a significant difference to the outcome of the Peloponnesian war for the Athenians. Nor was it his conclusion that the social damage of the period of the plague lasted much beyond it. Sociology trumped epidemiology, he appears to have thought. So the question today should be — what can sociology explain about the apparent resignation and passivity of the communities, ethno-racial groups or classes in the US now suffering disproportionately – unjustly they might say themselves — from Covid-19? The same question goes for the Europeans, the Chinese, the Russians.

This isn’t how Thucydides’ story of the plague is being interpreted, however. In the BBC version, the ancient Greek has been turned into an ode for ailing Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Boris Johnson poses with bust of Pericles, Athenian war-fighting general,

hero of Thucydides’ history, and casualty of the plague himself.

“He has faced stern challenges,” wrote an Oxford don called Armand D’Angour.

“[He] has experienced failure as well and success, and has benefited greatly from luck, no less than political skill. When, as is hoped, he makes a full recovery from Covid-19, perhaps busts of the historian Thucydides, the physician Hippocrates, and the philosopher Socrates, should join that of Pericles on his mantelpiece in No.10 Downing Street. In the US, according to this editorial of The Atlantic, Covid-19 is a test of American exceptionalism, and of the ideology of warfighting against everyone else, starting with Russia.

“The Great Plague tested this Athenian self-conception and found it wanting. Who people collectively believe they are is of the utmost importance, particularly in a democracy where the people are tasked with the grave responsibility of government. Self-government requires self-confidence. A democracy is unlikely to survive when the people have grown unsure of themselves and their leaders, laws, and institution…No amount of privilege or lack of interest can protect you from a pandemic. This is, by the way, something Thucydides noted.”

Anne Applebaum, who makes her living out of Russia warfighting, managed to apply a sociological cliché to the enemy, firstly China.

“Epidemics, like disasters, have a way of revealing underlying truths about the societies they impact. The Chinese have already paid a high price for the secretiveness of their system, and for the top-down bureaucratic culture that led many, initially, to conceal the disease.”

Russia, too, Applebaum followed in a tweet:

Source: https://twitter.com/

This is viral drivel, argues Neville Morley, a University of Exeter classics professor.

“Thucydides is a virus, spreading rapidly along modern channels of communication, turning those infected into dribbling zombies writing op-eds about how current events demonstrate the eternal relevance of Thucydides. Trust me, for I too have contracted this terrible disease, as well as observing others suffering from it. One simply has to look at the exponential growth in ‘what Ancient Athens can tell us about coronavirus’ articles over the last month. It’s the phenomenon known as secondary infection, with the virus seizing its opportunity with the ideal conditions for replication created by the present crisis. The curve doesn’t show any sign of flattening out; social distancing may help with Covid-19, but as we turn to the internet to relieve the monotony of isolation, we’re all the more susceptible to Thucyd-431

“… in the more acute form, sufferers develop a dangerous fever and sense of impending doom, casting off all restraint in their Thucydides-based predictions of the imminent collapse of society, the death of democracy, and the undermining of traditional values and national self-confidence. Even the historical information that Athens happily pursued its war for the next 27 years despite plague mortality, and that the overthrow of democracy was actually short-lived, brings no relief to such cases.”

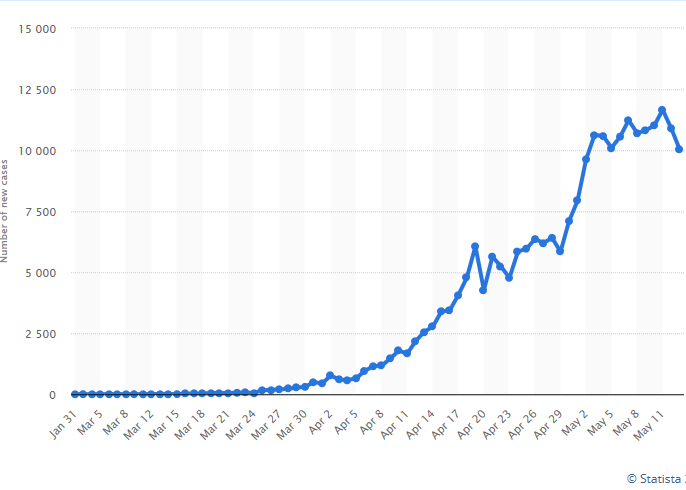

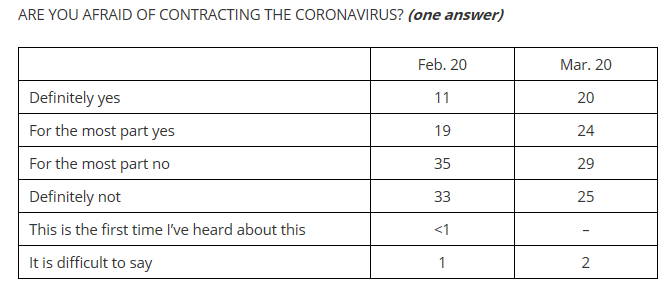

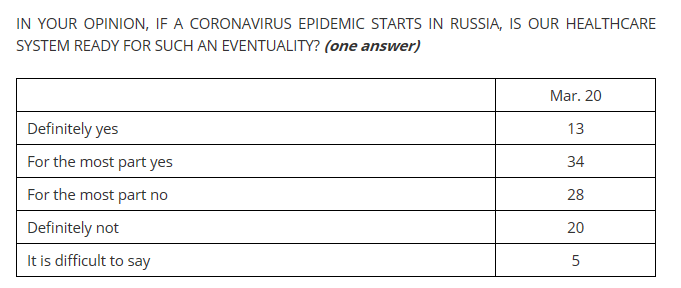

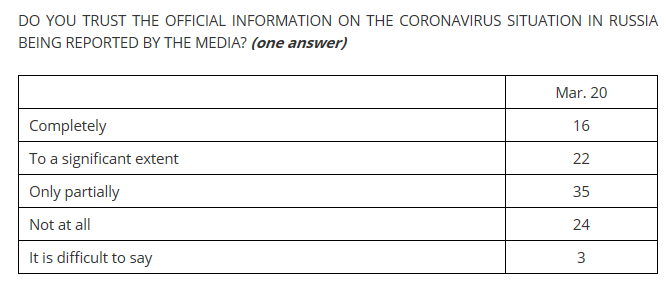

How are the Russians responding, and are they different from British, Europeans or Americans? The Levada Centre, an independent pollster based in Moscow, conducted a plague poll across the country between March 19 and 25, publishing the results in mid-April. At that time, the case infection numbers were very low and rising slowly.

THE GROWTH OF COVID-19 CASES REPORTED IN RUSSIA, JANUARY 31-MAY 13

Source: https://www.statista.com/

The take-off in Moscow was still a week away. The impact of Russian tourists returning from Italy, France and Spain – landing mostly in Moscow and St. Petersburg – had yet to incubate into the primary cases, and then infect their contacts exponentially. Still, the Russian apprehension was vivid — divided in half between scepticism and confidence in the capacities of the public health system to treat, and of the public authorities to tell the truth.

Source: https://www.levada.ru/

A follow-up nationwide poll on the corona virus was conducted by Levada between April 24 and 27, reported on April 30. In the Levada website release, two questions have been reported – the first asked if Russians are afraid of being infected; the second asked what change of behaviour they were adopting to deal with the threat. In the poll report, fear of infection was reported by 57%, compared to 44% the month before. Since March there has been a predictably large jump in those reporting they remain at home, avoiding public transport, regional and foreign travel, and also mass public events, as required by state policy.

Missing from the website is the Levada poll answer to a question of how satisfied Russians are with the performance of the President, federal government, regional and city officials in dealing with the pandemic. A report by Meduza, an opposition news site published in Latvia, says that 46% of Russians in the Levada poll approve the measures taken by the President and government against the coronavirus epidemic; 48% are dissatisfied with them; 30% consider them insufficient; 18%, excessive. There was slightly higher approval for governors and mayors, with 50% positive, 30% negative. Trust in both federal and local officials was lower in Moscow and other big cities than in rural areas.

Meduza published its report on April 30. Requested to provide the tabulations this week, Levada Centre refused without explanation.

Fearful and disapproving, or confident and trusting — these Russian polls reveal no Thucydides effect – no large change in belief; no improvement of political confidence in the state; no significant loss of confidence. If anything, the Russian evidence shows a reverse-Thucydides effect – that is, the reinforcement of beliefs the Russian public held before the onset of the pandemic.

According to the information warfare departments of the NATO states and their media, Russian public opinion is deeply alienated and disillusioned. The official information is false, they think their government is lying. In this Russian frame of mind, according to the newspapers of London and New York, the Thucydides effect is taking over, as it did in ancient Athens — an “attitude of utter hopelessness”. The Russian Foreign Ministry has reacted, calling this an “infodemic”. What evidence do the public health data provide?

Each day the federal government issues case numbers by city for total infections, recoveries, new cases over the previous twenty-four hours, numbers of tests administered, and deaths. There is no comprehensive public release of data on the number of the active cases in hospital by region, nor the number of those hospitalised who are in intensive care units (ICU) or on ventilators. Health Ministry officials say they are unable to provide these data privately. The Moscow city administration has announced that by the end of May it will have completed the installation of several temporary hospitals around the city with fresh capacity to accommodate up to 4,000 new cases.

Source: https://sputniknews.com/

This analysis, published on March 30 and thus early in the course of the pandemic, is the most accessible compilation of data on the availability at that time of hospital beds, intensive care units, and ventilators by region across Russia. Based on policy targets for intensive care units (ICU) and equipment planned by the Health Ministry since 2012, about 3% of the national hospital bed stock should be ICUs, or about 35,000 in total. The federal plan for ventilators has set a target of 1.5 more ventilators installed than ICU beds, or about 52,000.

In practice, by the start of this year, budget allocations and spending had fallen short — only Moscow, Kalmykia, Altai, and Komi had reached the standard of 3%. ICU beds in St Petersburg have been dwindling over the past five years; the deficit in relatively poorer regions is obvious and acknowledged by public health officials. The safety and efficacy of ventilation equipment are also highly variable.

In Moscow, with a concentration of two-thirds of the nationwide total of tested infections, the acceleration of new hospital equipment stock has been faster than elsewhere, though not exclusively so. “Starting from the end of February, regional authorities began to report the results of capacity calculation at meetings dedicated to the corona virus. It turned out that in practice, counting the regions, the number of ventilators exceeds 4.5% of the total number of beds only in Moscow, Khanty-Mansiysk, Samara, Penza, Kalmykia, and Amur; close to this level in St. Petersburg, Karelia, Tatarstan, Kirov, and Ulyanovsk. In all other cases, the deficit is up to twice or more.”

MODELING THE RUSSIAN COVID-19 DEFICIT, MOBILIZING TO MEET IT

Calculating the demand for hospital care with projections of corona

virus infection of 20%, 40% and 60% of the population over 19 years of age, by region.

The Moscow policy, like the national policy, has been to squeeze the growth of infected cases by contact restriction,and at the same time increase the number of hospital beds and equipment to meet the demand. The supply-demand model for this anticipates that 20% of identified cases will need hospitalisation, and 5% of them will go to ICUs. At Moscow’s current reported level of just over 100,000 active cases, about 20,000 beds are required; about 1,000 ICUs, about 1,500 ventilators.

On May 11, in his most recent conference with the pandemic administrators, President Vladimir Putin reported a surplus of capacity over demand:

“The number of specialised hospital beds equipped for treating severe cases was increased from 29,000 to 130,000, and we have built up equipment and supplies reserves, including a reserve capacity of ventilators, which has critical importance for us. Thank God, of course, that so far we have had to use only a small fraction of this stand-by capacity.”

Source: http://en.kremlin.ru/

Putin added: “your plans must take into account the real situation on the ground, ensure strict requirements for safety, the protection of people’s health and lives, and must be based on the verified assessments of the level and degree of the potential threat. The final say rests with the doctors and specialists.”

Putin’s last line marks a neo-Soviet revolution in Russian policymaking.

The irrelevance of Thucydides starts with his admission that “the doctors were quite incapable of treating the disease because of their ignorance of the right methods” and the failure of “any other human art or science.”

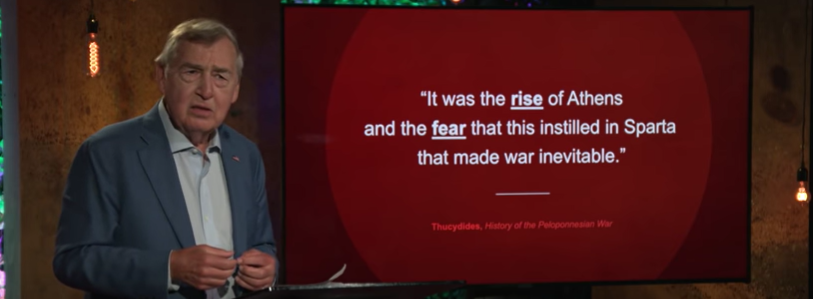

The promotion of Thucydides today is also Anglo-American warmaker ideology. Tagged the “Thucydides’ Trap”, this is the idea that when a rising power threatens a ruling power, war between them is inevitable; and for that reason war is likely to be started pre-emptively by the ruling power. In Graham Allison’s book, first published in 2017, he fabricated this out of the sentence at the start of Thucydides’ history: “What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta.”

Allison’s inevitable war was between the US and China; Allison hadn’t caught up with the Russia-China-Iran-Ukraine-Venezuela-Libya combination for war on Washington’s target screen at the moment. The book recommends all the forms and targets of US warmaking with the exception of those which Allison suspects Washington might lose. His real purpose was to advocate US warmaking without that risk. So he started himself with pre-emptive info-war.

Allison is a professor at Harvard University whose career to date has been distinguished from his fellows by the Thucydides mistake on China he’s proud of; and by a second which he tries to hide; that’s been his Russia mistake.

Graham Allison (left); excerpt from Thucydides’ history which Allison has called the “Thucydides Trap” making it a fresh alibi for US war-making (right). Source: https://www.youtube.com/ (November 2018).

Allison’s “Thucydides’ Trap” is a fake, according to all the experts on ancient Greece who have examined it for years. Applying his “Thucydides Trap” to Russia, Allison has been an advocate of cold war, proxy war, sanctions war, info and cyber war – with not a single US mistake detected so far.

Allison is less proud of having been the only Harvard professor to have gone to work for the Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, for the purpose of selling Deripaska’s shares in his Russian Aluminium (Rusal) company to unsuspecting or suspicious US investors. That story was reported in 2007, when Deripaska was failing to get the UK regulators to approve the listing of his company on the London Stock Exchange. Allison accepted the Deripaska Trap, but refused to answer questions about why.

Thucydides wasn’t as blasé or as shy.

No comments:

Post a Comment